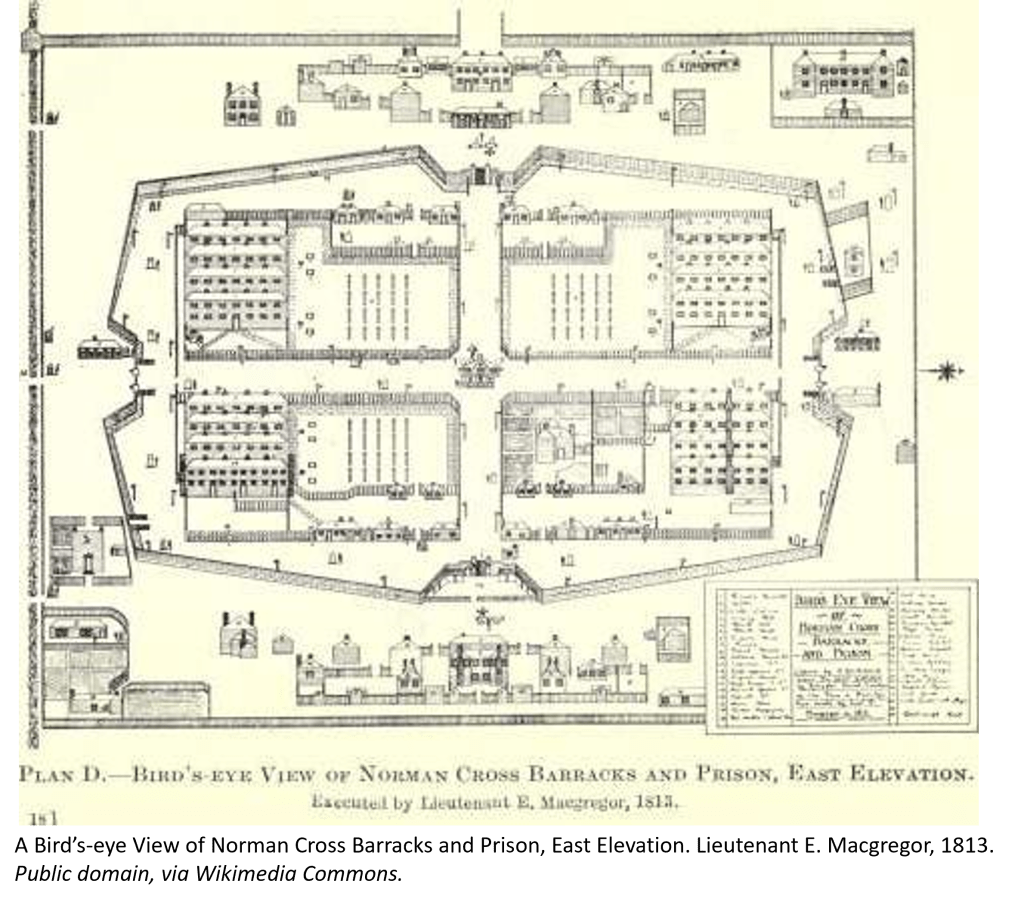

West of Peterborough, along the Great North Road in Cambridgeshire, the first purpose-built prisoner of war camp was constructed near the hamlet of Norman Cross in 1796. Designed to hold prisoners from the French Revolutionary Wars, and later Napoleonic Wars, Norman Cross Depot averaged interring around 5,500 prisoners from across Europe before it was demolished in 1816. The site covered almost 15 hectares, surrounded by brick walls and guard towers. The prisoners lived in wooden barracks crowded throughout the site, at one time holding almost 7,000. Conditions were not grim, but it was a prison.

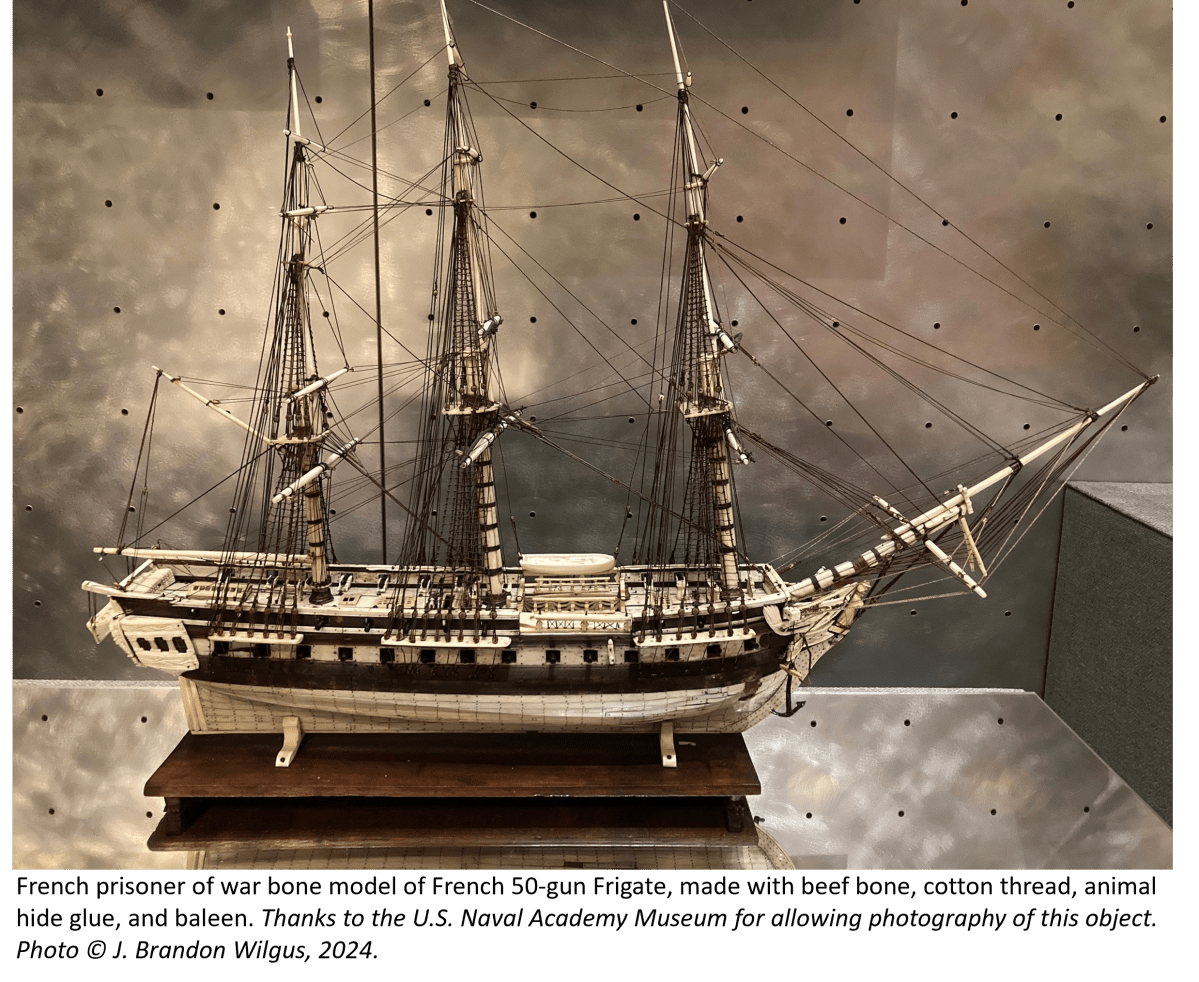

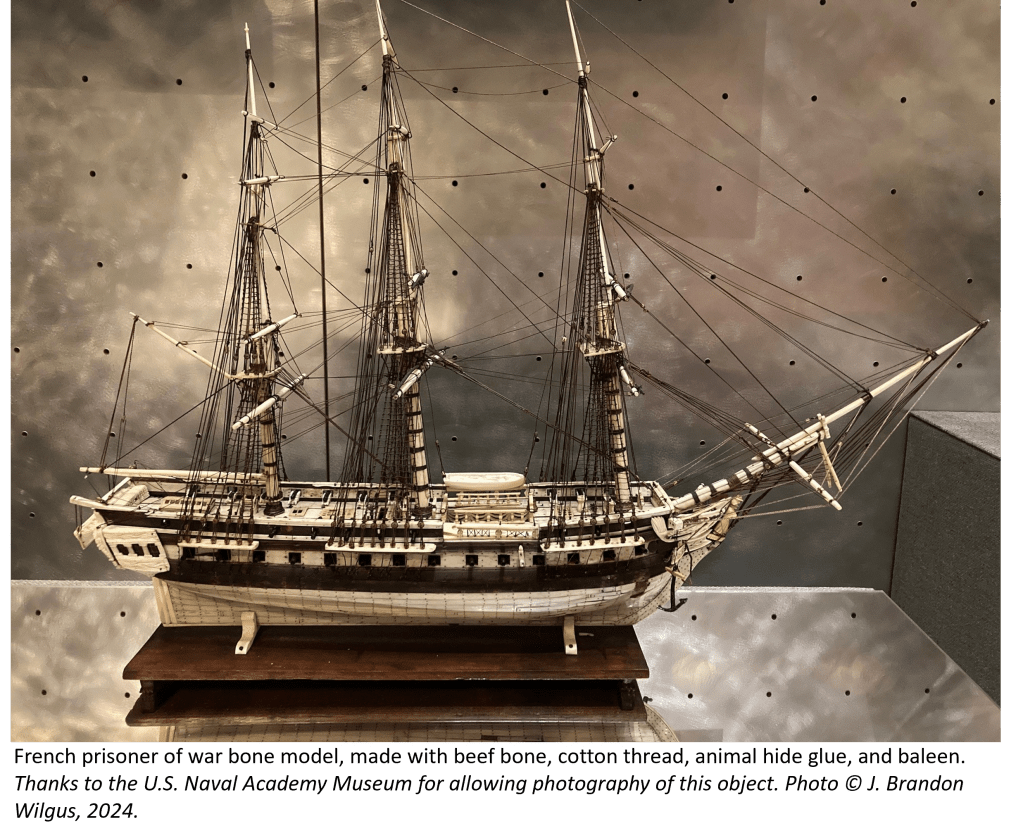

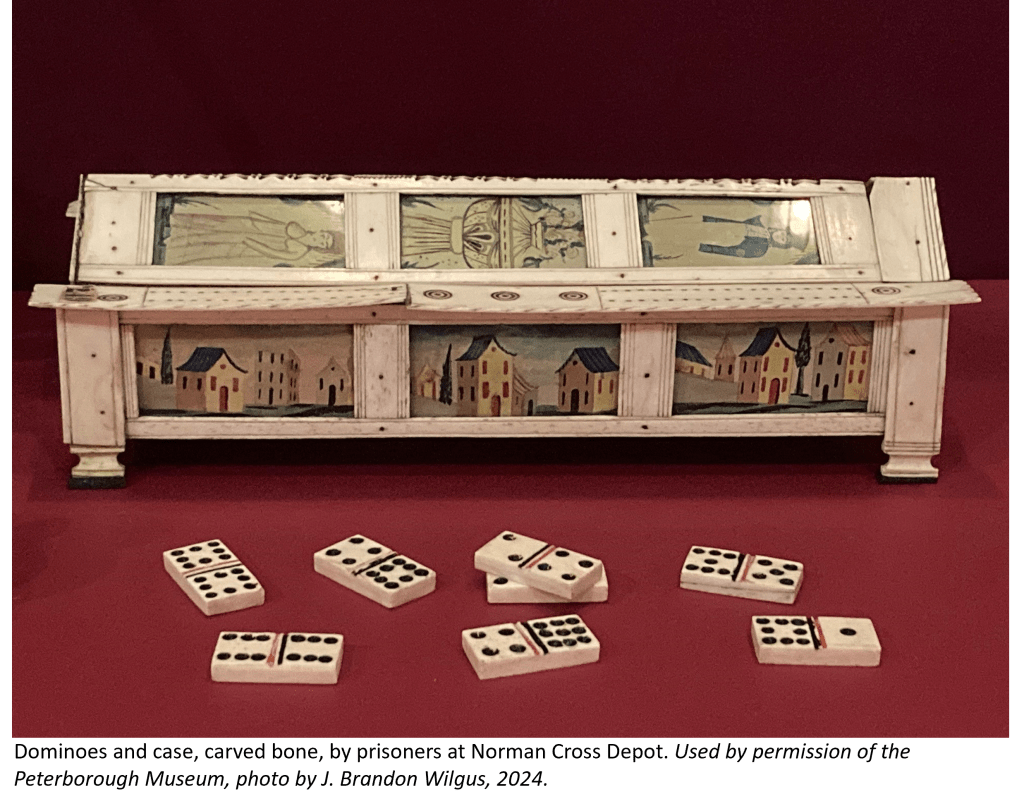

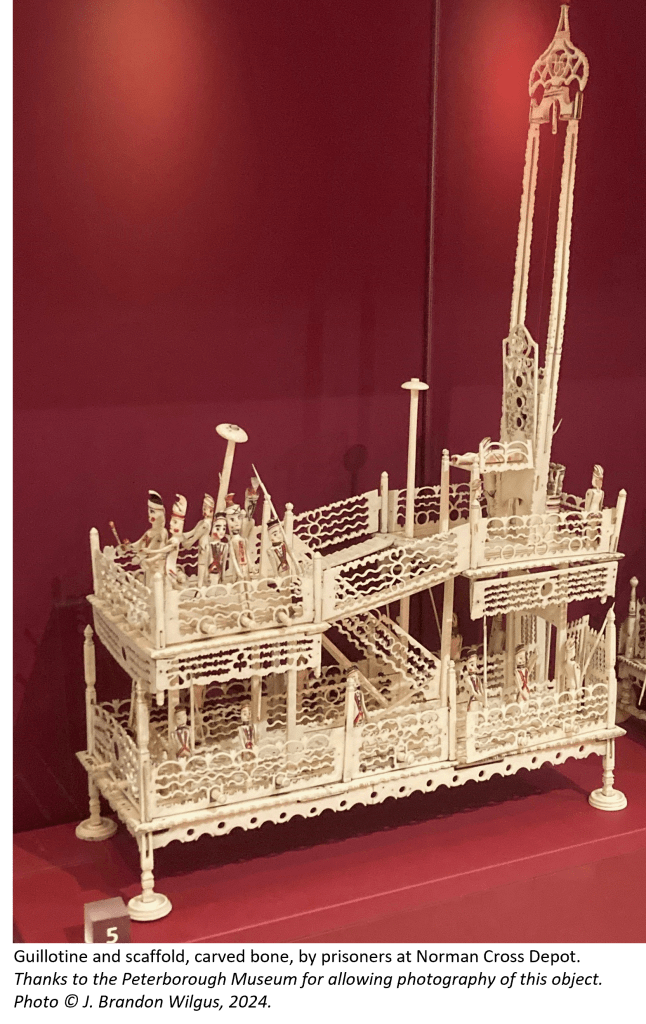

French, Spanish, Dutch, Italians, Germans, and Poles all ended up in the camp, guarded by local Cambridgeshire militia. Many of the prisoners were French, Spanish, and Dutch sailors, captured from Royal Navy victories on the high seas. Administered by the Admiralty, it may not surprise you that the Royal Navy recruited sailors from the Norman Cross Depot, seeing an opportunity to address manning shortfalls with knowledgeable seamen – and many of the captives were happy to leave. However, most of the prisoners stayed for years in the camp seeking ways to pass the time, keep busy, and possibly make some money. During its twenty years of existence, the prisoners of Norman Cross made beautiful art, mainly from the soup bones, straw, baleen, and wood they could find or acquire around the prison or from locals. These men, to pass the time and to make art which they could sell, created magnificent pieces which are highly prized today. This artwork, a type of scrimshaw or an early version of trench art can be seen at various museums and in private collections from the United Kingdom to the United States.

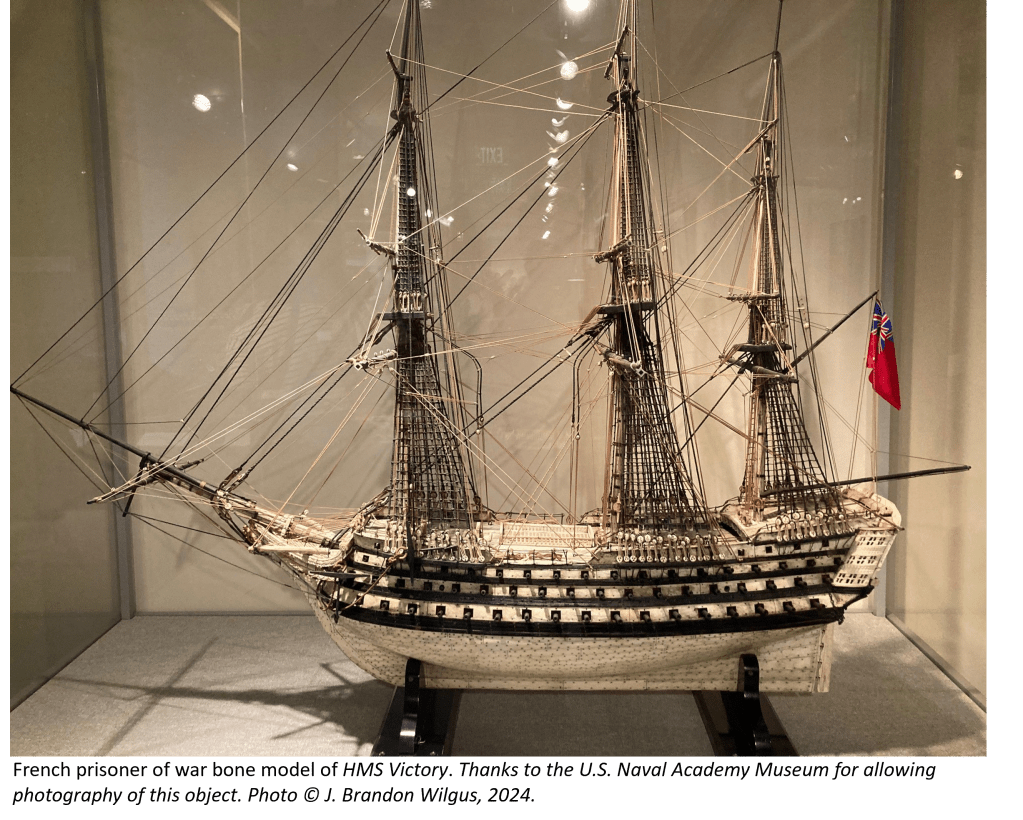

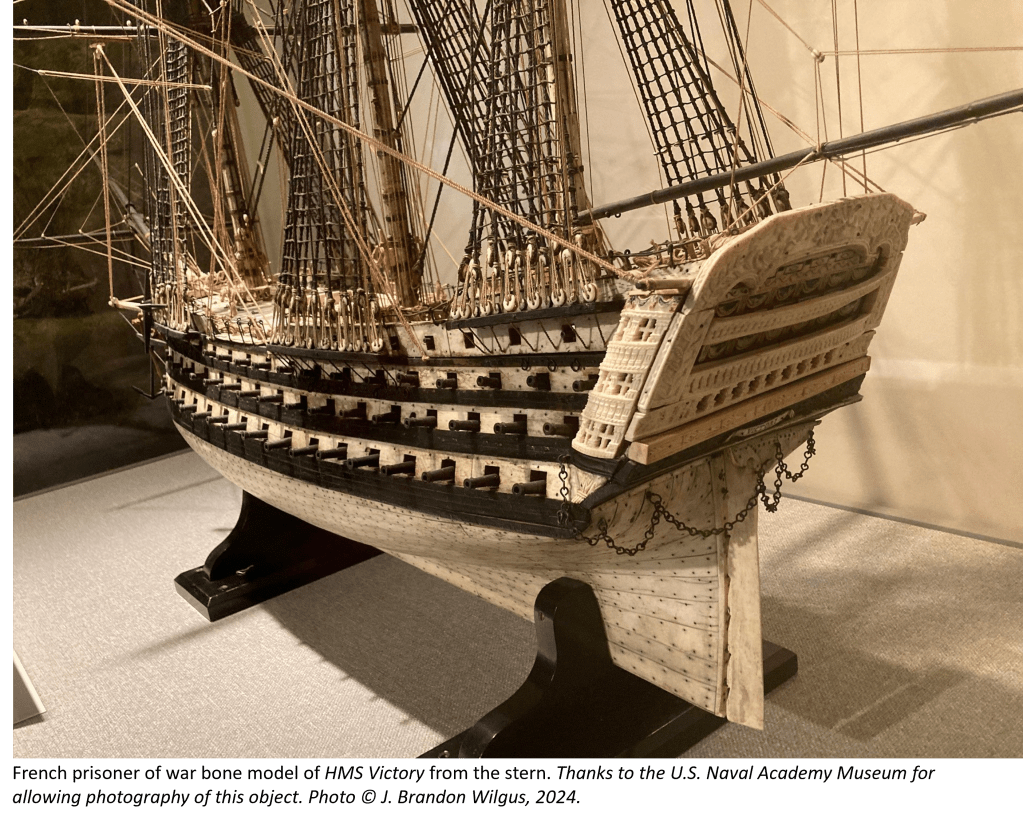

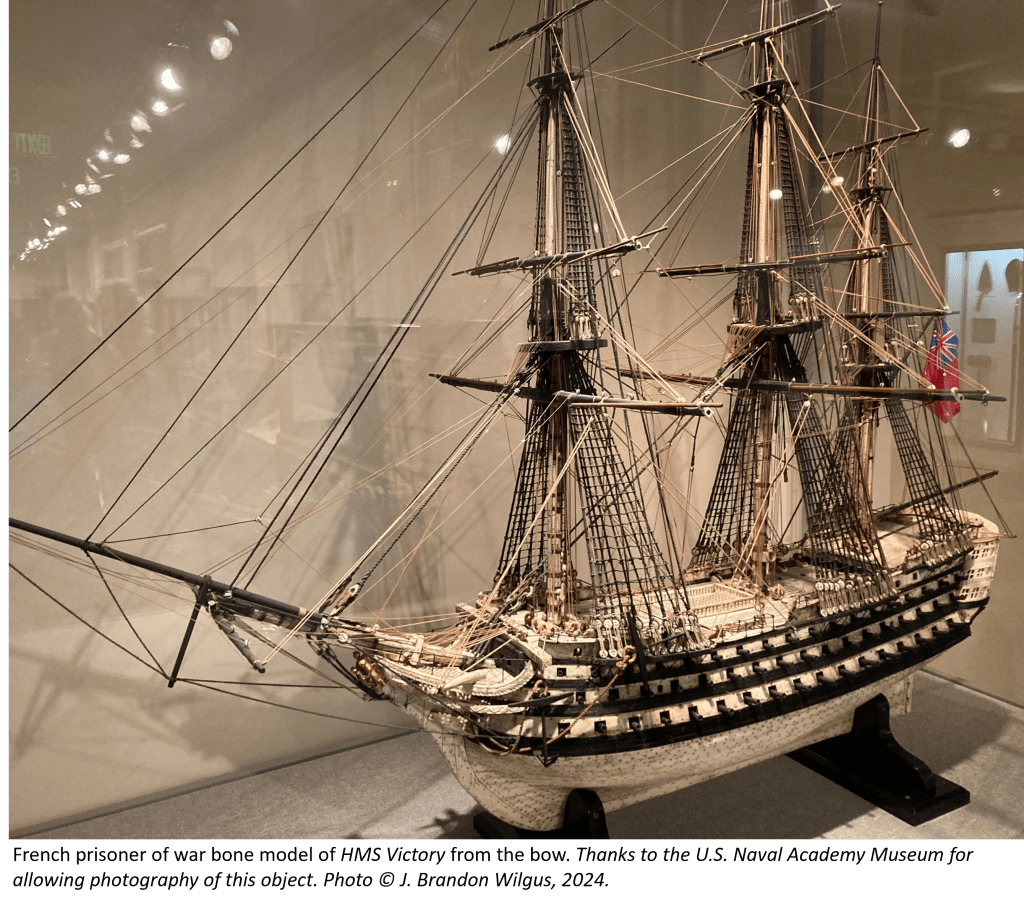

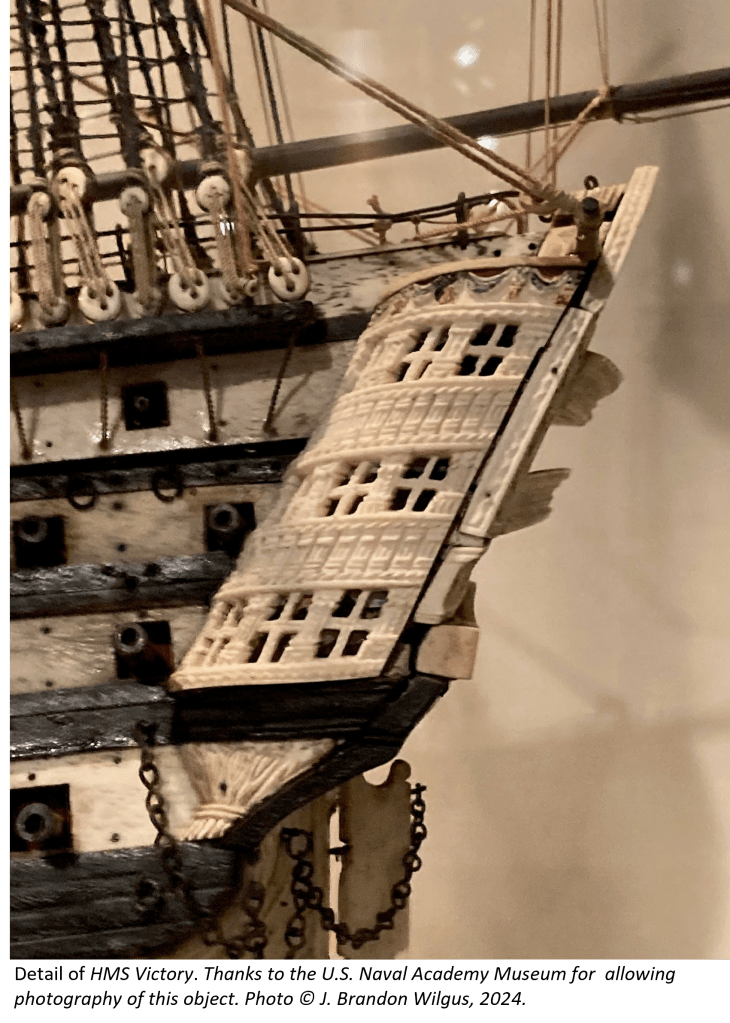

Although I have wanted to write about the artwork made at Norman Cross for several years, many outstanding examples of this craft found their way to the United States in the late 19th Century, with important pieces ending up at the U.S. Naval Academy in Anapolis, Maryland. It was only recently that I was able to visit the Museum at the U.S. Naval Academy where I could see these works – and the treasured masterpiece which emerged from the skilled hands several French sailors – the model of HMS Victory which holds pride of place in Annapolis.

The Art.

The prisoners carved and sculpted with materials on hand: bones, straw, wood, turning these everyday items into fabulous pieces of art. The prisoners carved what they knew, or remembered of their home and ships they sailed on, with an aim of selling their artworks in a local market which became popular around the camp. Sailors carved bones into ships, often with their yardarms shortened so that the models would fit nicely on a mantlepiece. Rigging was made from memory, often incorrectly and sometimes even overly complicated to show off the intricacies of their craftmanship. Straw and wood were split and dyed, then glued into exquisite marquetry. Scaffolds with guillotines, dollhouses, games, and even automatons were created and then sold. This flourishing of prisoner art came to an abrupt end after Waterloo in 1815, when the prisoners were sent home and the camp demolished a year later and returned to farmland.

HMS Victory.

As mentioned before, the largest, most exquisite item created at Norman Cross Depot is undoubtedly the model of HMS Victory. According to the curators of the US Naval Academy Museum, after the defeat of the combined French and Spanish Navies at Trafalgar on 21 October 1805, fifteen French prisoners of war began the model of Nelson’s triple-decked flagship. It took them two years to complete the ship, aided only by prints from newspapers and their own memories of general ship’s design. In 1807, the model was complete and at several feet tall was seen as a wonder at the time. The Lords of the Admiralty organised the purchase of the model from the French prisoners, the amount paid is forgotten, and then presented the model to HM George III. The King then had the model placed on top of Nelson’s tomb – the hero of Trafalgar who died onboard HMS Victory – in the crypt of St. Paul’s Cathedral, London, where it sat for 27 years, before it was removed and cleaned in 1834. Once it was removed, it was never returned to Nelson’s crypt. In 1915, during the height of the First World War, an American millionaire financier and sailing enthusiast, Edward Francis Hutton, purchased the model and brought it to the United States where it set in his private collection. In 1980, the model was in the posession of the Maitland family which gave HMS Victory to the U.S. Naval Academy where it now resides.

How to visit the old prisoner of war camp:

The site of the Prisoner of War Camp lies about six miles west of Peterborough. Exit the A1(M) on the A15 and head east toward Yaxley. At the southwest corner of the old camp, there is a large column, the Norman Cross Monument, crested by a bronze Napoleonic Eagle. Built and sited in 1914 by the Entente Cordiale Society, the monument was sadly toppled and the eagle stolen in 1990. An appeal was made, and the column was repaired and moved due to the A1 being expanded in the late 1990s. Now rebuilt, a bronze replica of the Napoleonic eagle was restored to the column. His Grace, the Duke of Wellington, unveiled the monument on 31 October 1998. The monument is dedicated to the 1,770 prisoners who died at the camp between 1796 and 1816. In the winter of 1800 to 1801, a typhoid epidemic swept through the camp, leading to the death of 1,020 prisoners, and several hundred others would pass away over the years the camp was open. This monument honors these men’s demise. There is parking available as well as an information board at the column.

To the North and East of the old camp, now agricultural land, were burial sites for the prisoners who died at Norman Cross. In 2009, Wessex Archeology joined with the archeologists of Channel 4’s Time Team, led by Tony Robinson, to dig at Norman Cross. The team of archeologists discovered graves, carved items, and even a set of dominos. The episode titled “Death and Dominoes: The First POW Camp” aired on 3 October 2010 and is worth watching. The Wessex Archaeology report can be viewed here as well.

Part of the brick prison wall still stands nearby but is incorporated into the private property of residents.

To view the prisoner’s artwork:

Visit the Peterborough City Museum, Priestgate, Peterborough PE1 1LF. There is no parking at the museum, so I’d recommend parking at the Queen’s Gate shopping center’s car park and walking. Navigate to: PE1 2AA. The Museum is also an easy walk from the Peterborough train station. For more information, see their website: https://peterboroughmuseum.org.uk/. The museum is free and has a fine collection.

If you are in Annapolis, Maryland, in the United States, the U.S. Naval Academy’s Preble Hall is the location of the museum, one of the world’s great naval collections. The prisoner’s artwork is located on the top floor. For more information, see their website: https://www.usna.edu/Museum/index.php where several other pieces of prisoner art can be viewed. The museum is free.