The Eighth Wall Art Conservation Society was an active group in Cambridgeshire in the 1980s. The EWACS, as they styled themselves, saved many works of art from the Second World War from derelict buildings on abandoned airfields. They preserved these works for us today, and while some are available to be viewed by the public, others have been hidden away and forgotten.

At the Bottisham Airfield Museum, one can view a mural of the RMS Queen Mary which was saved by EWACS in the 1980s. The men of the 361st Fighter Group sailed on the Queen Mary from the United States to England in 1943 and one of the airmen painted an image of the ship directly on the brick walls of one of the airfield’s buildings. This mural eventually found its way to the museum to be appreciated by all.

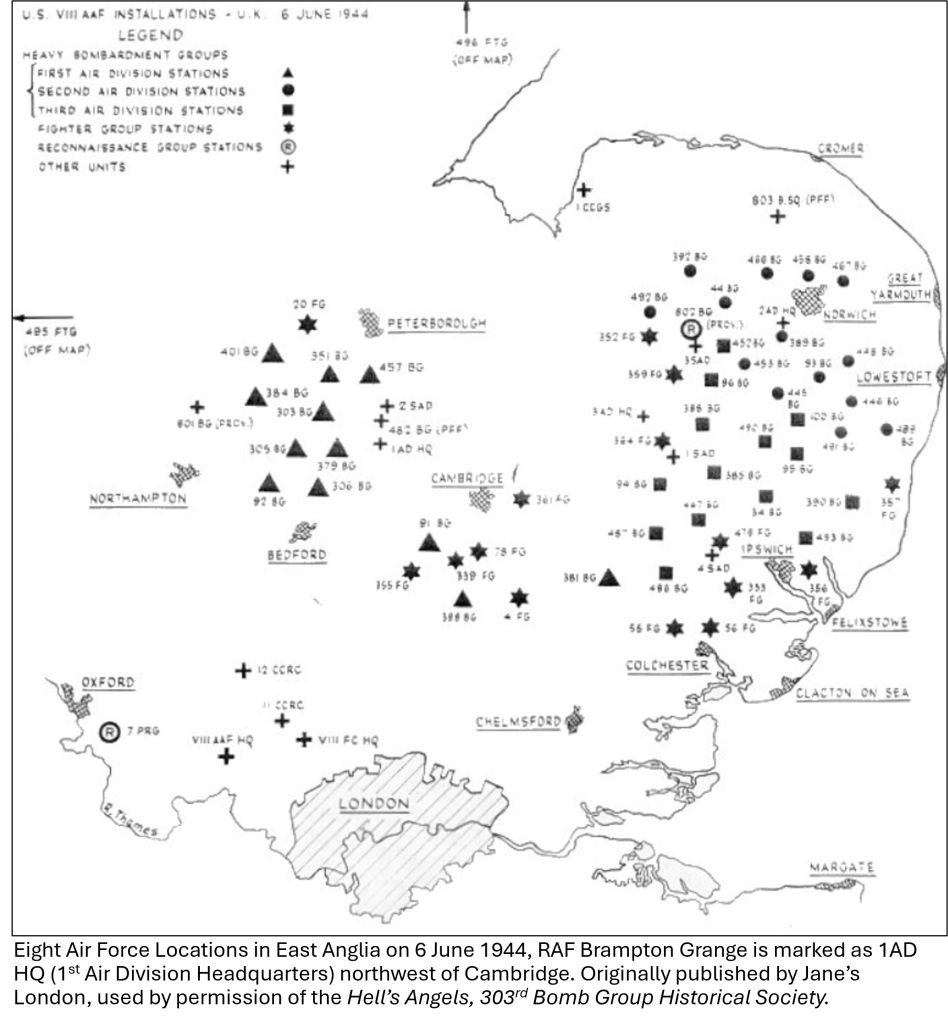

Originally prepared in 1940 as a satellite of RAF Waterbeach, RAF Bottisham was at first a grass relief field for the Cambridge based de Havilland Tiger Moths of No.22 Elementary Flying Training School. As the war went on, several other RAF aircraft would fly from the field which gradually grew and expanded. In 1943, Bottisham was turned over to the U.S. Army Air Forces’ 361st Fighter Group. The 361st Fighter Group’s squadrons first flew the Republic P-47 Thunderbolt but transitioned to the North American P-51 Mustang in May 1944. The fighters from the 361st Fighter Group, recognizable with their yellow painted engine cowlings, escorted the bombers of the 8th Air Force to their targets in occupied Europe, including the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses of the 303rd Bomb Group based at RAF Molesworth.

This may seem a winding thread: the EWACS, RAF Bottisham, the 361st Fighter Group, and RAF Molesworth – but in the March 1983, the EWACS volunteers, supported by U.S. airmen stationed in the area, rescued several paintings from the old enlisted men’s club at RAF Bottisham before the building’s demolition. At the time, the Bottisham Airfield Museum did not exist and these volunteer conservators sought out a home for this saved art and turned to a growing U.S. Air Force base in the area: RAF Molesworth.

At Molesworth, in a small break room, the EWACS installed three saved pieces of wall art from RAF Bottisham: a mural of a B-17 with a Messerschmitt Bf-109 diving in pursuit, two glasses of wine coming together in a cheer, and a slogan painted in cursive. The slogan, painted across the bricks reads: “Here’s a toast to those who love the vastness of the sky.” Sadly, these murals can only be seen regularly by the men and women stationed at RAF Molesworth as part of the U.S. Visiting Forces and are not regularly available to the public.

One of EWACS saved wall paintings ended up at the Imperial War Museum branch at RAF Duxford in Cambridgeshire. At Duxford, the wall mural “Poddington Big Picture” is displayed in Hangar No. 3, it displays a expertly detailed B-17 from the 92nd Bomb Group which flew from RAF Podington in Bedfordshire. One of the few signed pieces of wall art, we know the “Poddington Big Picture” was painted by George C. Waldschmidt. A few additional saved murals were shipped to the 8th Air Force Museum at Barksdale Air Force Base, Louisiana, USA. Others are dispersed in museums and displayed throughout East Anglia.

While it is a pity that these beautiful murals at RAF Molesworth are not available for the public to view, we are thankful for the volunteers of the EWACS who worked to save and conserve these beautiful pieces of Cambridgeshire’s aviation history almost forty years ago. In 1983, Dick Nimmo, Bill Espie, and Brian Cook, all volunteers with EWACS removed and brought these works of art to RAF Molesworth before the derelict enlisted club at RAF Bottisham was demolished. We owe them a debt.

To read more about wall art from the Second World War: https://heritagecalling.com/2019/05/17/war-art-military-and-civilian-murals-from-the-second-world-war/

The Guardian published an article in May 2014 regarding USAAF art from the war with some excellent pictures: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2014/may/17/art-usa

The Airfield Museum at RAF Bottisham houses the mural of the Queen Mary and many other fascinating items, for more information about the museum: https://www.bottishamairfieldmuseum.org.uk/

To learn more about the USAAF at RAF Bottisham during the Second World War, visit: https://www.americanairmuseum.com/archive/place/bottisham

For more information on RAF Molesworth, visit: https://www.americanairmuseum.com/archive/place/molesworth

For more information on RAF Waterbeach’s museum, which is certainly worth a visit: http://www.waterbeachmilitarymuseum.org.uk/index.html

For the murals at the 8th Air Force Museum in Louisiana, a few photos are available at their website: https://8afmuseum.com/