It has been brought to my attention several times that Cambridgeshire has seen few battles and holds no remembered battlefields – a real problem for a historical blog on the military history of Cambridgeshire. Some argue that for all the fighting which has occurred in England, from the Romans to the Danes, through the Civil War, Cambridgeshire has remained an area of relative peace. While there have been consequential battles near Cambridgeshire – one thinks of Naseby (1645) in Northamptonshire or the Battle of Fornham St Genevieve (1173) near Bury St Edmunds in Suffolk – they have all occurred outside the borders of the county. The conventional wisdom is that Cambridgeshire has been spared the war and bloodshed which has been sadly common in English history. This is not true! Allow me to write about one example:

Towards the end of the English Civil War, in July 1648, a battle occurred first along the River Great Ouse and then spilled into the market square of St Neots in Cambridgeshire. Now, you are certainly thinking that the Civil War had concluded with the defeat of King Charles I’s army in May 1646 and that the period between the Spring of 1646 and Charles’ execution at the Banqueting House in London at the end of January 1649 was one of relative peace. Again, not true! After the defeat of the Royalists, England settled into a period of uneasy peace with the restive New Model Army under the leadership of Sir Thomas Fairfax and Oliver Cromwell and the more moderate parliamentarians trying to find a way to maintain the monarchy and negotiating with Charles I. As negotiations broke down, it became obvious that Charles and his advisors were playing for time to seek assistance from Scotland. The Second English Civil War began as uprisings in England and Wales allowed the Scots to rise and invade from the North. During this time, a royalist cavalry troop of several hundred men under Colonel John Dalbier, a German mercenary who had fought with parliament before changing sides, arrived near St Neots after a failed attack on London. The Royalists had two confidants of Charles I in their party: Henry Rich, the Earl of Holland, and George Villiers, the 2nd Duke of Buckingham, both also escaping the recent fighting near London. The approximately 300 Royalists were tired, demoralized and fleeing their failure outside London, chased by parliamentarian dragoons. Once arriving at St Neots on 9 July, Colonel Dalbier posted a few guards at the bridge over the River Great Ouse while his men pitched camp and slept within St Neots’ Market Square. The Earl of Holland and Duke of Buckingham found rooms at an Inn and stayed apart from the men.

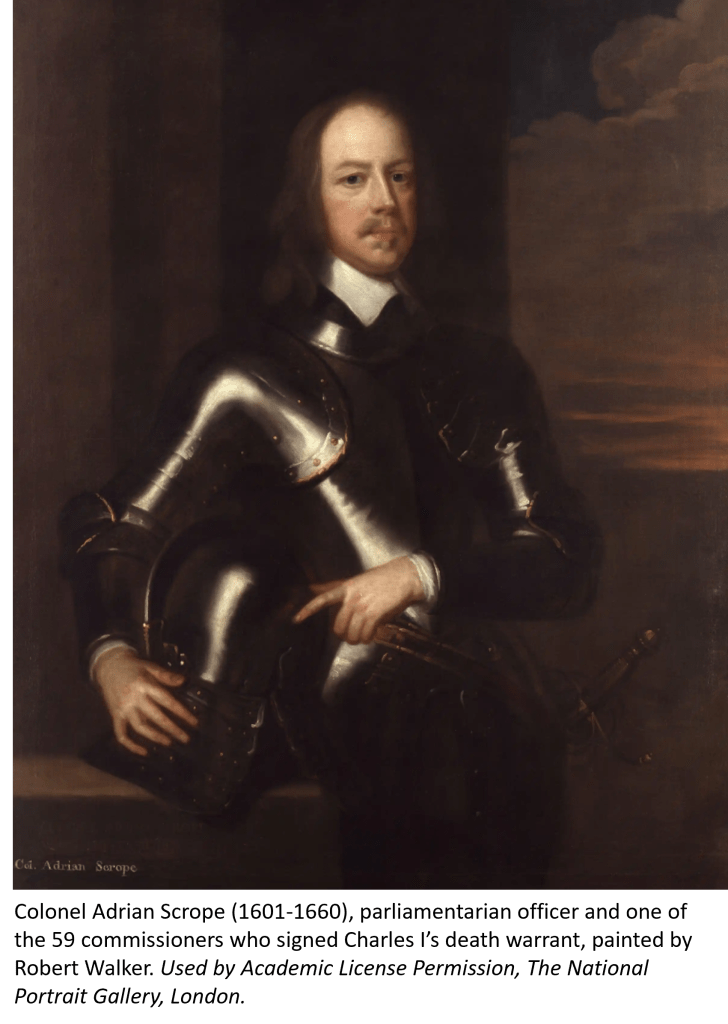

Having defeated the royalist force near London, the leadership of the New Model Army sent parliamentarian Colonel Adrian Scrope with a mounted force of approximately 100 dragoons and foot soldiers to chase and intercept the royalists fleeing London. Having caught up to the royalists at the River Great Ouse, Colonel Scrope’s men waited until the early morning hours to engage. At 2am on the morning of 10 July 1648, the parliamentarians attacked the few awake men of Colonel Dalbier first at the bridge, and then in a moving battle into the heart of St Neots – the Market Square. Colonel Dalbier died near the bridge along with several of his men, some of whom drowned in the Ouse trying to swim away in the dark. The Earl of Holland roused his men and fought the parliamentarians in the Market Square, but as his resistance buckled, he fled into the Inn where he had billeted for the night and barricaded himself within. The Inn’s gate was broken down by the attacking soldiers. The parliamentarians stormed the Inn and cornered the Earl in his room, sword drawn, back against the wall. He surrendered once he had received the soldiers’ promise that his life would be spared. He was brought to Colonel Scrope, who had him chained along with five other captured royalist officers and imprisoned in St Mary’s Parish Church. They were taken to Warwick Castle the next day under armed guard.

The Duke of Buckingham escaped, fleeing into the night with some portion of the cavalry in the direction of Huntingdon. Eventually he would make his way to the Netherlands and would rise to great power during the restoration of Charles II.

After the battle, captured royalist forces were held overnight in St Mary’s Parish Church, though several fled into the dark and dispersed. As mentioned, the Earl of Holland was taken to Warwick Castle the next day where he was held for the next six months. He had already been pardoned once in 1643 when he changed sides during the Civil War, deserting his friend the King to join parliament, before rejoining the royalist cause. Detested by the more extreme parliament of 1649 and by Colonel Scrope in particular, his machinations finally caught up with him, the Earl of Holland was held for six months before being tried for treason and executed on 9 March, shortly after Charles I.

Colonel Scrope went on to sign Charles I’s death warrant as one of the 59 commissioners and served as the head of security during the King’s trial. He was promised clemency during the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660, but was arrested as a regicide and hanged, drawn and quartered at Charing Cross, London on 12 October 1660.

Today, the St Neots Market Square where the royalist forces camped and most of the fighting occurred is still the centre of the town and easy to visit with ample parking. The St Neots Museum is a few steps away along New Street and worth a visit. Sadly, the 17th Century stone bridge where Colonel Dalbier stood watch was torn down and replaced in 1964. St. Mary the Virgin Parish Church, which has been called the Cathedral of Huntingdonshire, is stunning. Built mostly during the 15th Century, though there are earlier sections, the church is beautiful and worth a visit to appreciate its late medieval architecture and 128-foot tower; however, I was unable to find any memories of the royalist soldiers, their officers, and the Earl of Holland who were held there in 1648 after the Battle of St Neots.

For more information, visit the St Neots Museum, which is open Tuesday through Saturday each week. The Museum is located at The Old Court, 8 New Street, St Neots, PE19 1AE. 01480214163.

As is the case with most churches in Cambridgeshire, St Mary’s Parish Church is open daily for visits.