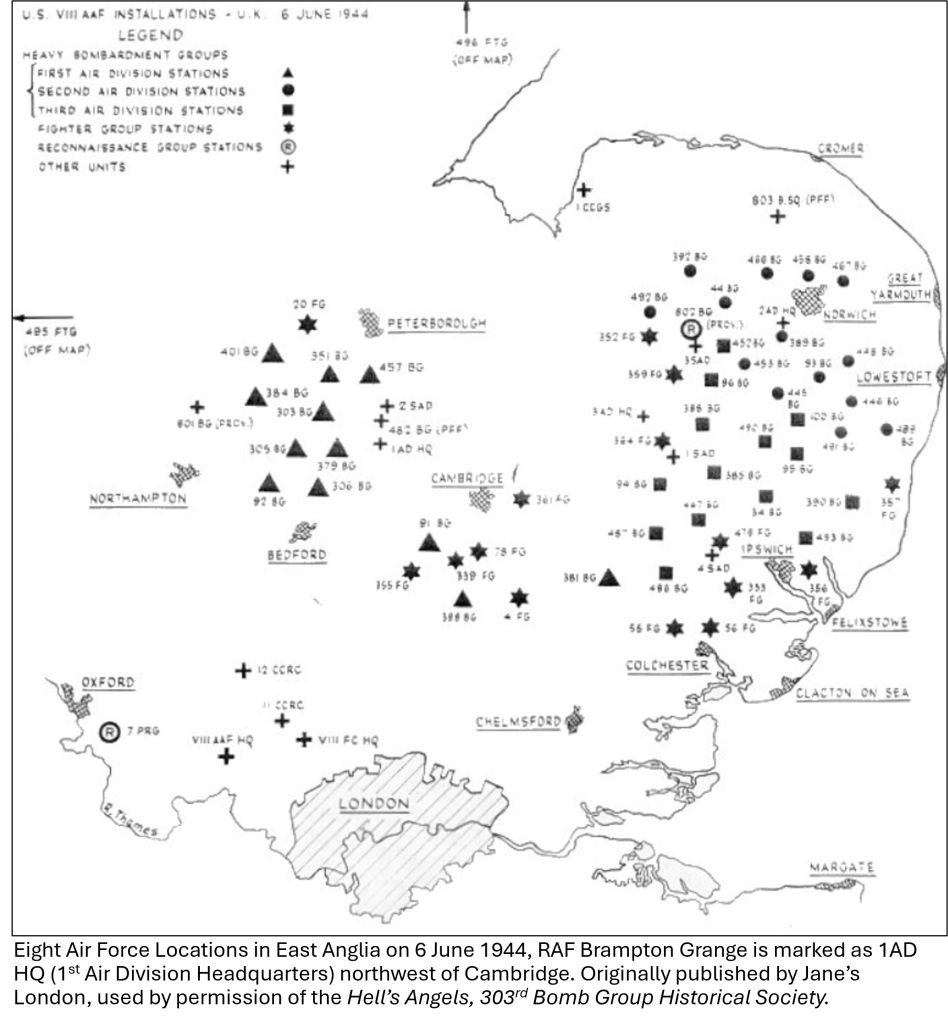

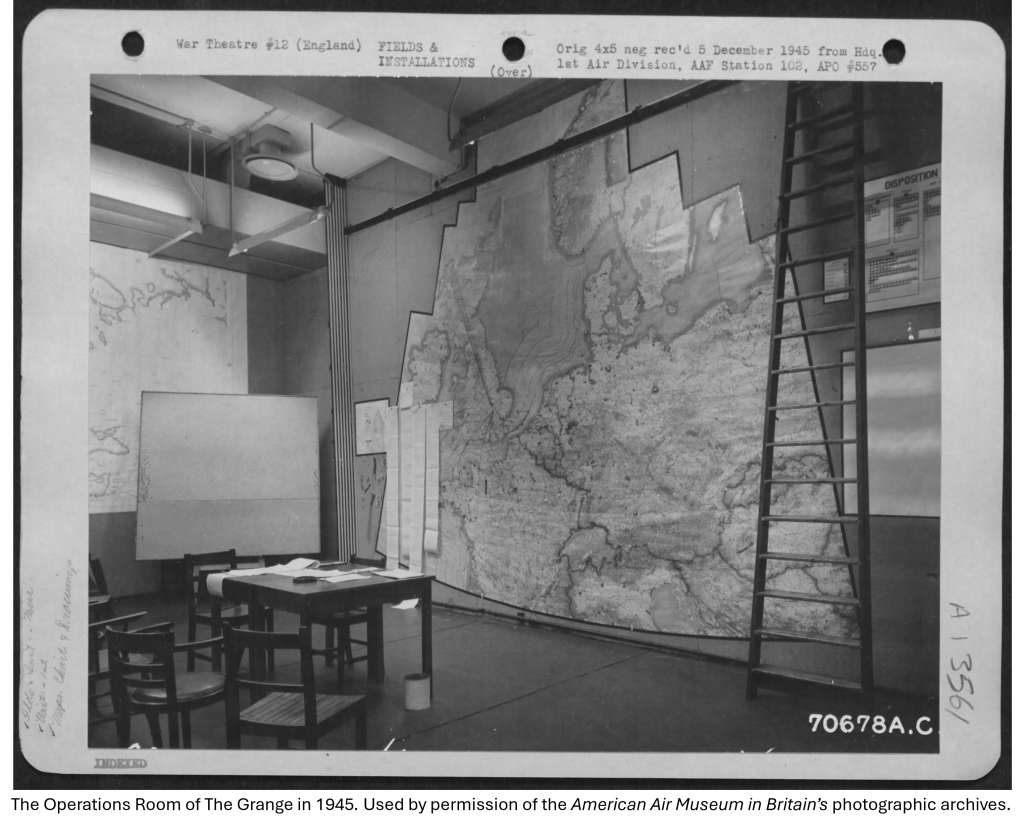

During the Second World War a large Royal Air Force Station operated several types of aircraft and served both the Royal Air Force and the U.S. Army Air Corps near the village of Little Staughton, on the border between Bedfordshire and Cambridgeshire. In 1942, RAF Little Staughton was designed as a Class A airfield, able to support the heavies — multi-engine bombers such as Boeing B-17s, Consolidated B-24s, and Avro Lancasters. Once complete, the airfield was set aside as a depot, more specifically, the 2nd Advance Air Depot of the US Army Air Corps, under the 1st Bomb Wing at RAF Brampton Grange (see my posting about this headquarters). B-17s, damaged or in need of maintenance that could not be provided at their home station were flown to RAF Little Staughton for repairs.

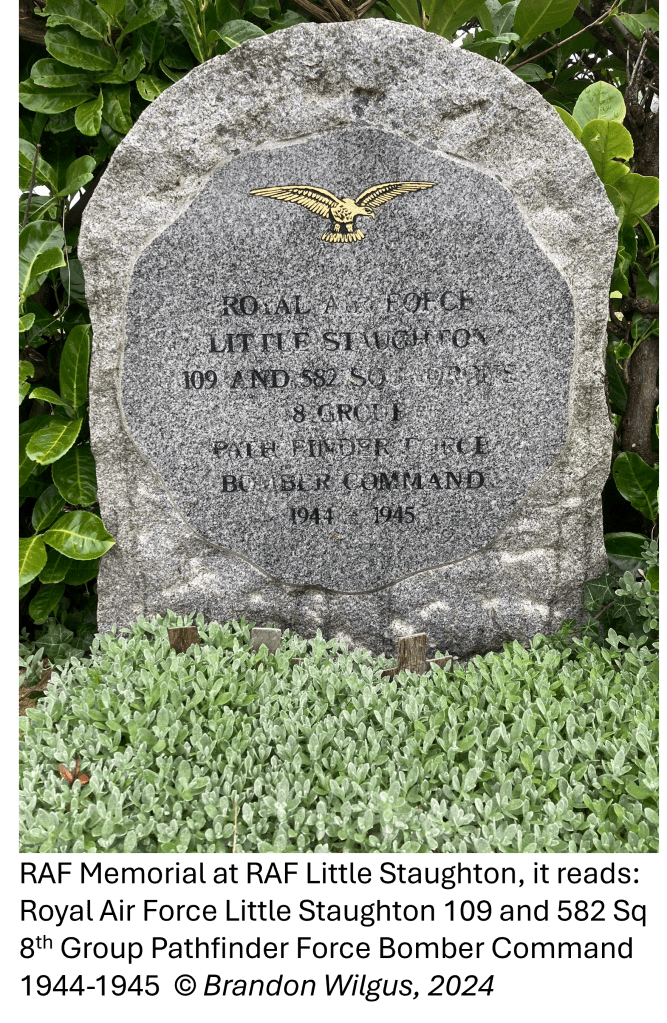

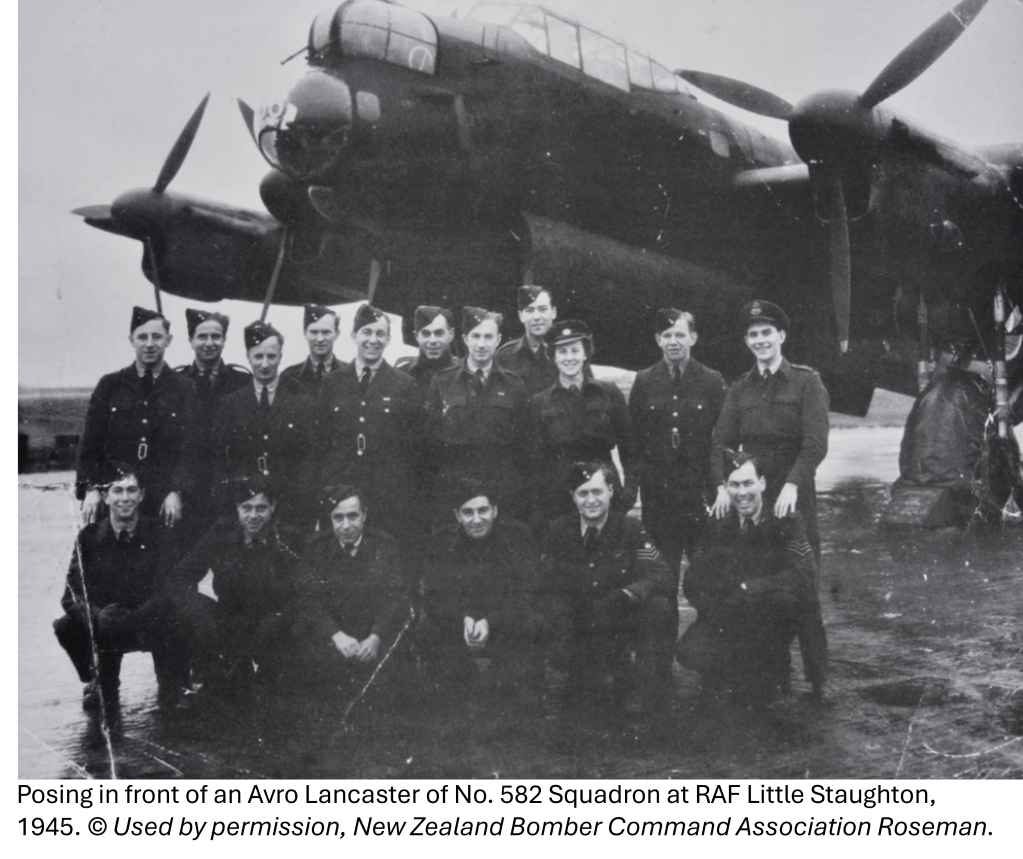

On 1 March 1944, the U.S. Air Force returned the facility to RAF use, and it became the home of two squadrons of Pathfinder Force Group 8 – No. 109 Squadron flying the de Havilland Mosquito XVIs, and No. 582 Squadron flying Avro Lancaster Mark Is and IIIs.

In the last year of the war, the Pathfinders flew 2,100 sorties from RAF Little Staughton in 165 separate missions against Germany and occupied Europe. Over 120 medals for courage and gallantry were awarded to the officers and men flying from RAF Little Staughton, along with two Victoria Crosses: Squadron Leader Robert A. M. Palmer, VC DFC with Bar and Captain Edwin “Ted” Swales, VC DFC. The two men were close friends and both pilots in 582 Squadron.

Squadron Leader Palmer was 24 years old on 23 December 1944 when he was the Master Bomber – in command of the lead bomber on a raid of 30 aircraft – over Cologne, Germany. Despite heavy clouds and several losses enroute to the target, Palmer continued the run despite an order having gone out to break up the formation and for the bombers to drop their ordnance visually. His Lancaster damaged by German anti-aircraft fire, with two engines erupting in flames, Palmer stayed on target and dropped his bombs as the lead plane, fulfilling his role as a Pathfinder, before his aircraft spiralled out of control. Only the tail gunner escaped from Palmer’s Lancaster. He was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross. Six of the 30 RAF aircraft on the 23 December 1944 raid on Cologne were lost.

Captain Swales, a South African pilot, was 29 years old on 23 February 1945 when he was the Master Bomber in a Lancaster leading a bombing raid on Pforzheim, Germany of 367 Lancasters and 13 Mosquitos. Swales successfully found the target and marked it for the several hundred bombers following his lead. After dropping his bomb load, Swales’ Lancaster was critically damaged by a Messerschmidt Bf-110. With the fuel tanks ruptured and two engines lost, Swales held the plane in the air as his crew all successfully bailed out over France. He attempted to bring down the Lancaster over friendly territory, but it stalled and crashed near Valenciennes. Like his friend Palmer, Swales was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross. His Lancaster was one of 12 lost in the raid.

28 Lancasters from No. 582 Squadron would be lost from April 1944 until VE day. 23 Mosquitos of No. 109 Squadron were lost during the same period. The sacrifices of these men, working to protect their nation and liberate Europe, in such a short period of time is stunning.

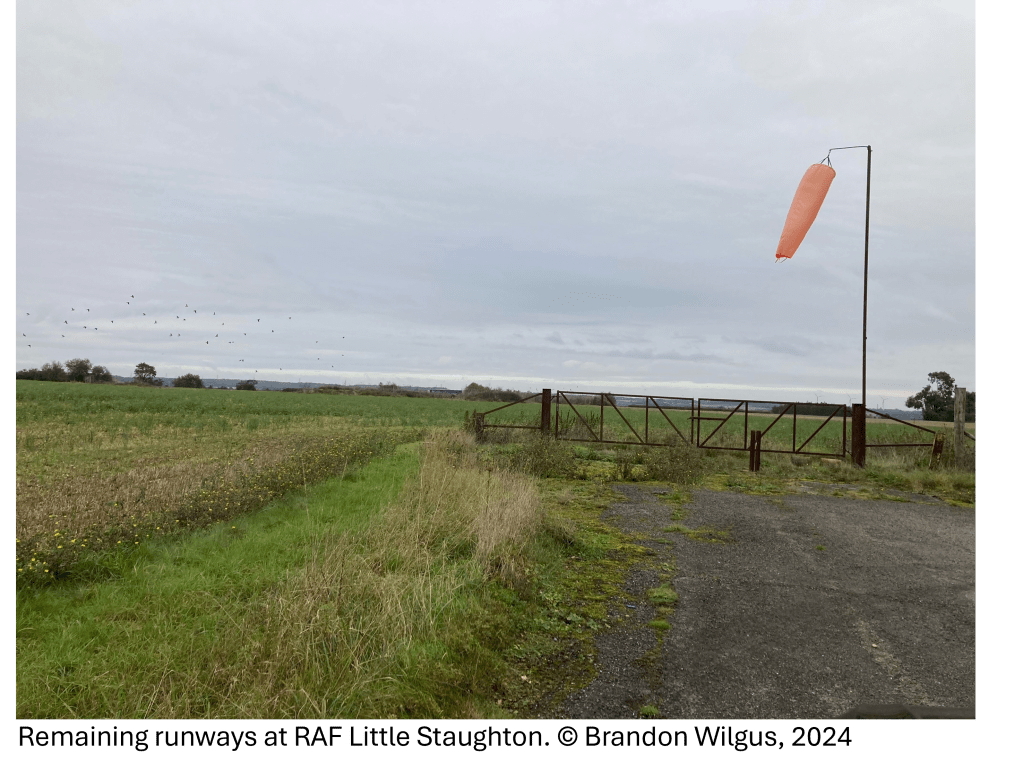

In September 1945, RAF Little Staughton was put into a care and maintenance status. However, its days as a flying airfield were not finished. In the 1950s, the U.S. Air Force expanded and lengthened the main runway to 3,000 yards so that RAF Little Staughton could serve as a divert for RAF Alconbury’s North American B-45 Tornado multi-engine jet bombers and the Douglas B-66 Destroyer light bombers which were then flown by the 85th Bombardment Squadron.

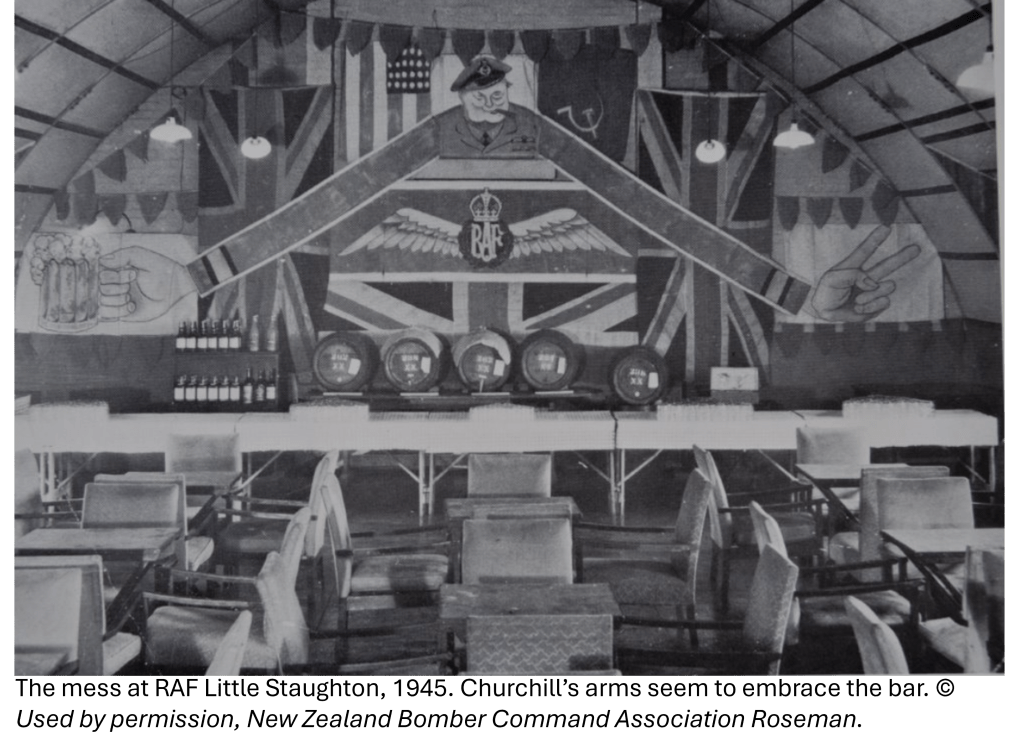

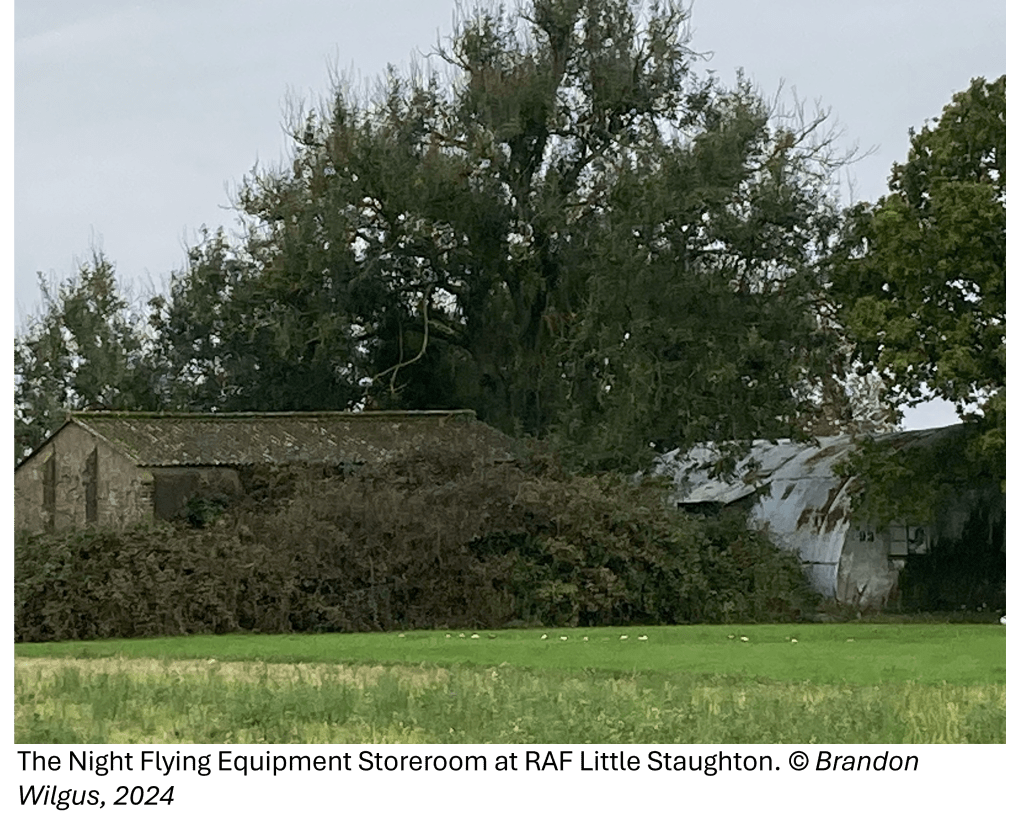

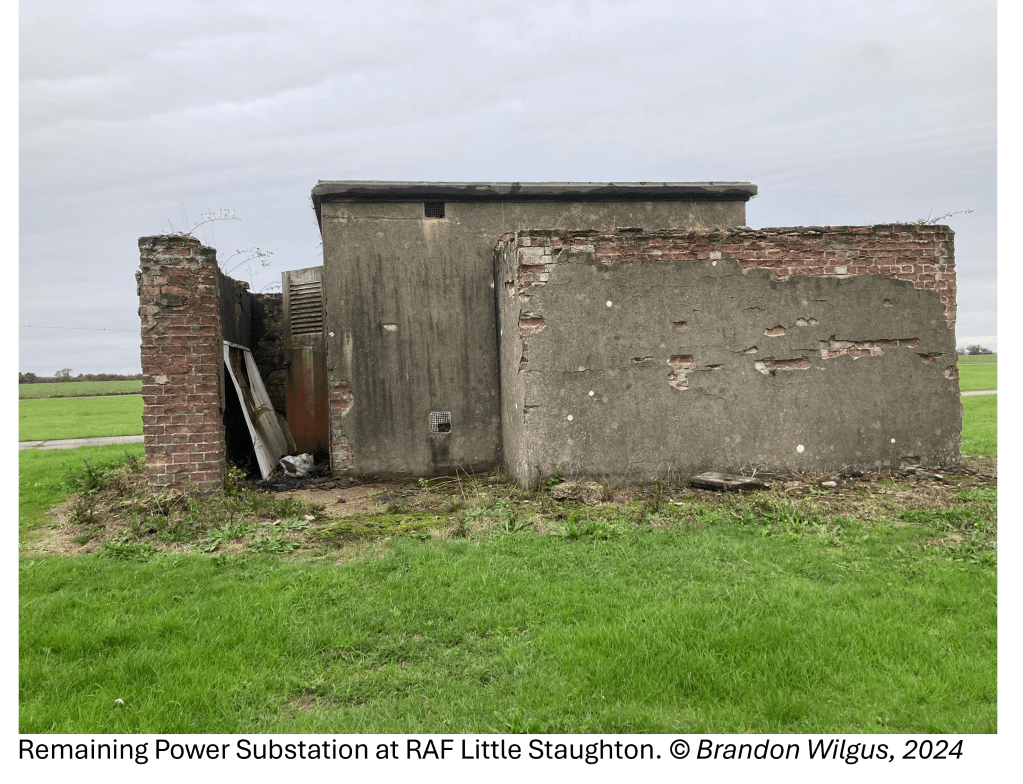

Today, light industry dots the former airfield and many of the original buildings, storage areas, hangars, and the control tower still stand. A solar power farm covers much of the land which once was the Royal Air Force station. Overgrown and scattered around the site are several old blast shelters, bomb dumps, petrol storage tanks and more. Hangars and barracks are still used by small businesses. Light, general aviation craft fly from the old runways. Maybe, best of all in terms of preservation, the World War II control tower still stands and is in excellent shape, it is now a private residence. In fact, RAF Little Staughton is one of the best-preserved airfields I’ve visited, not that it has been kept as a museum, but its ongoing use has maintained the facility in an impressive state of repair after almost a century.

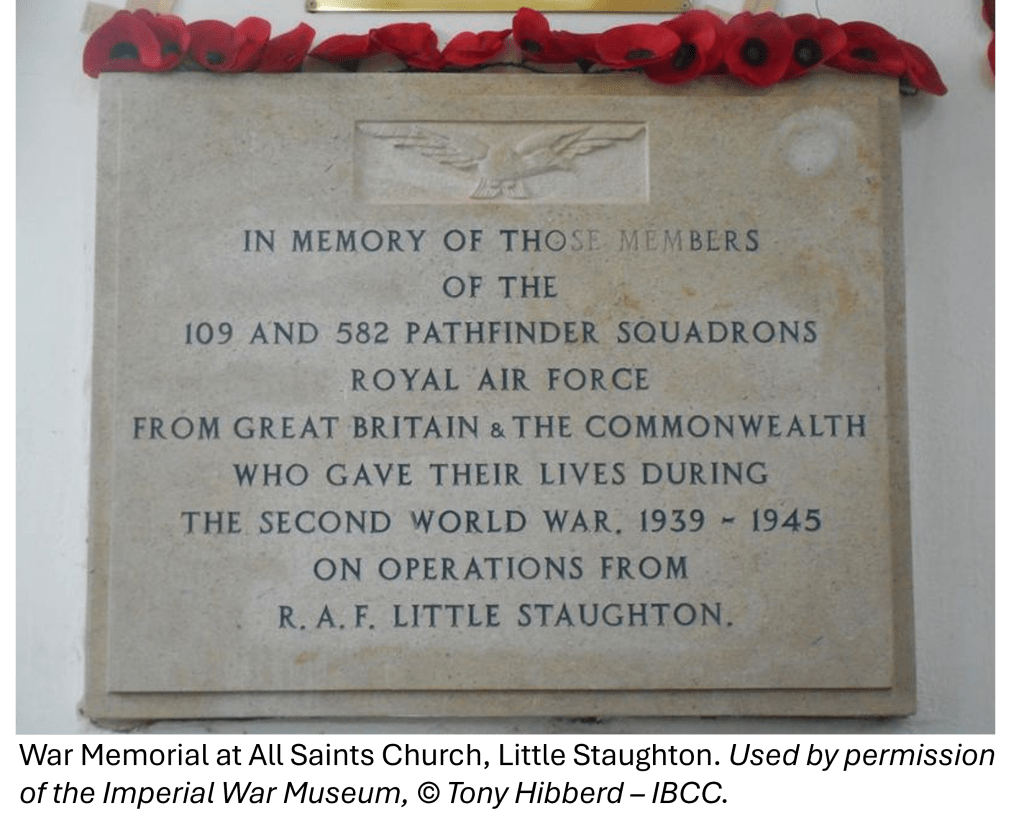

A mile or so from the former air station lies the Parish Church of All Saints, Little Staughton. Interestingly, the church lies a bit distant from the village, as the original village was abandoned after a bought of bubonic plague and the survivors farther away from its original location in the Middle Ages. A memorial in the Church on the south wall honours the men from 109 and 582 Pathfinder Squadrons who lost their lives, and the airfield’s Roll of Honour is on display as well. (Although the church is open on Saturdays and Sundays in the summer, you can ring ahead and arrange a time to visit throughout the year, just check the parish website.)

Located near the end of the runway is the RAF Little Staughton Airfield Memorial, obviously well cared for by the village. It recognized the sacrifice of the airmen who once flew from this field and lies on the cracked concrete which once made up the runway.