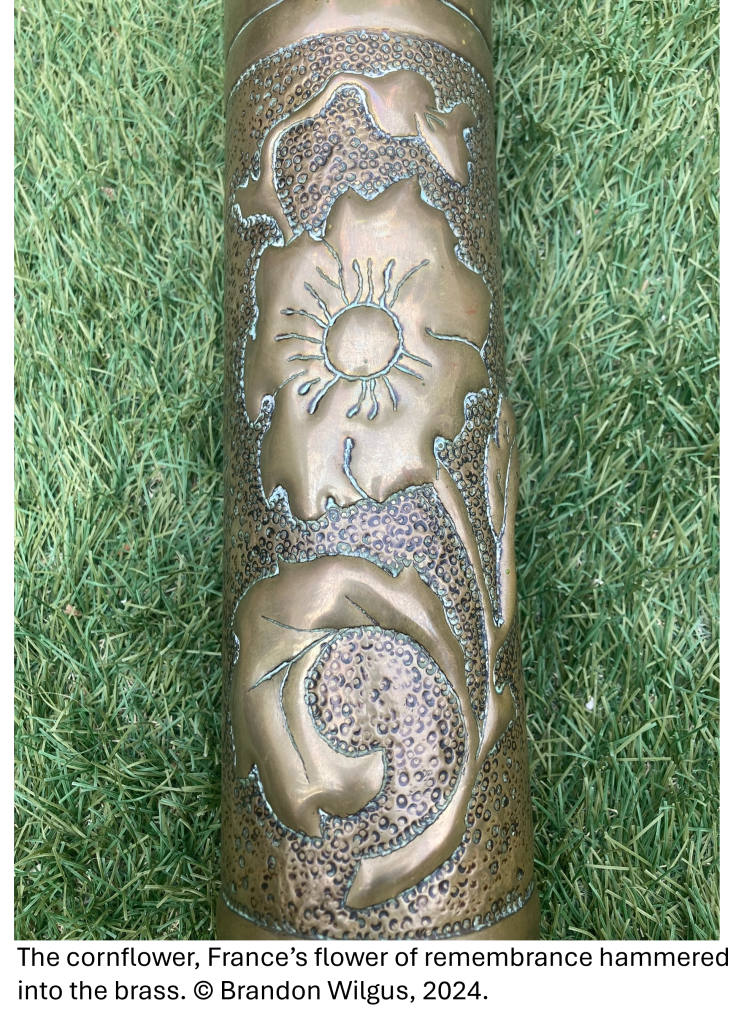

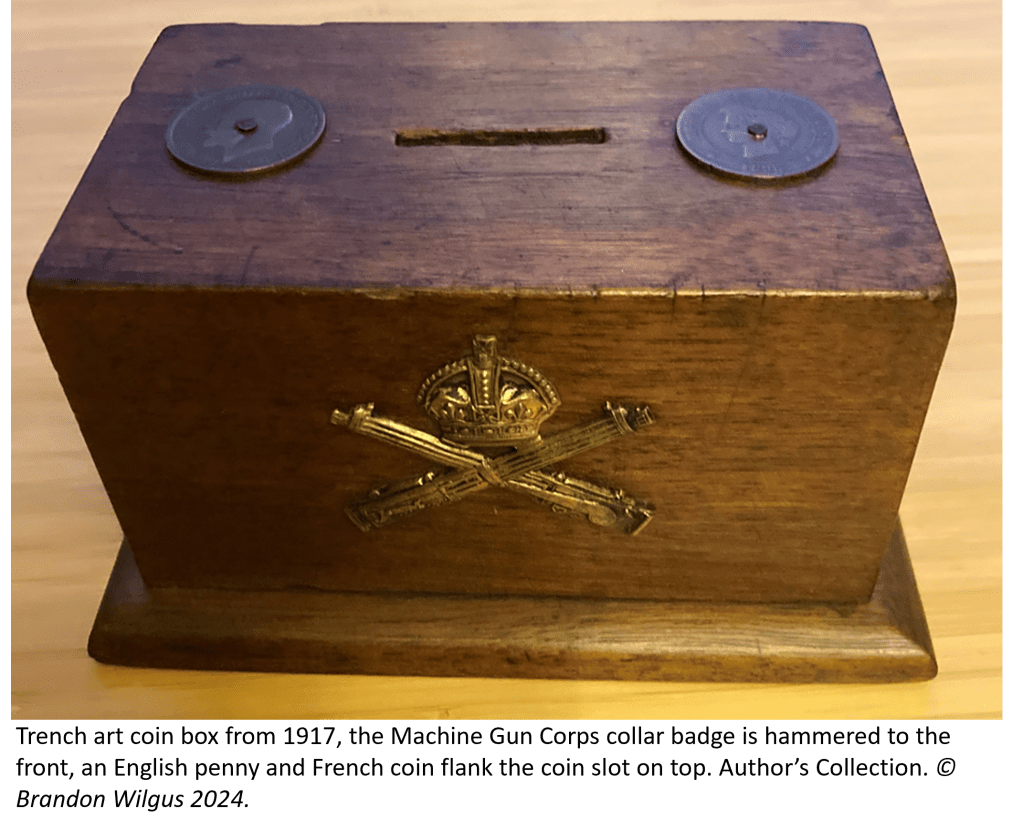

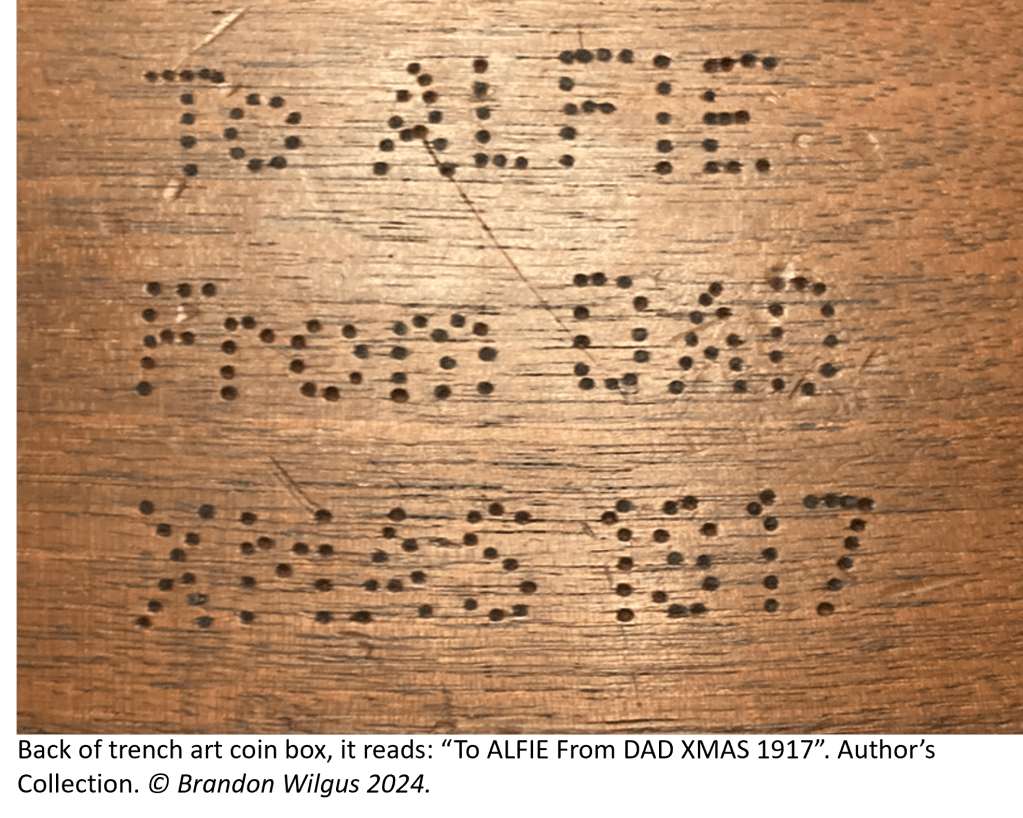

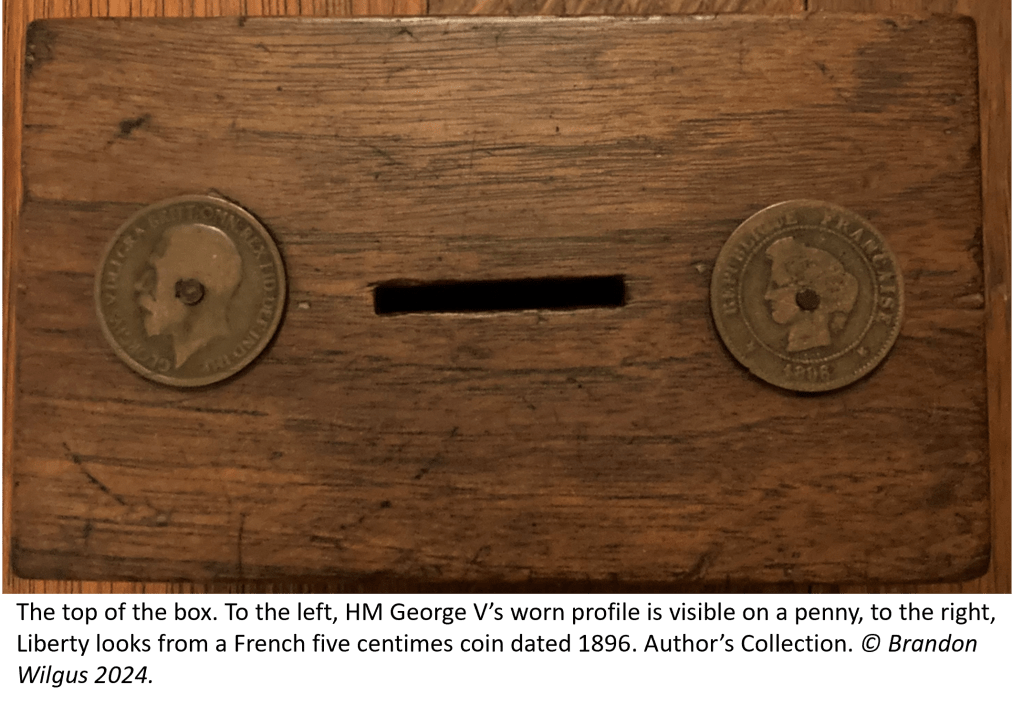

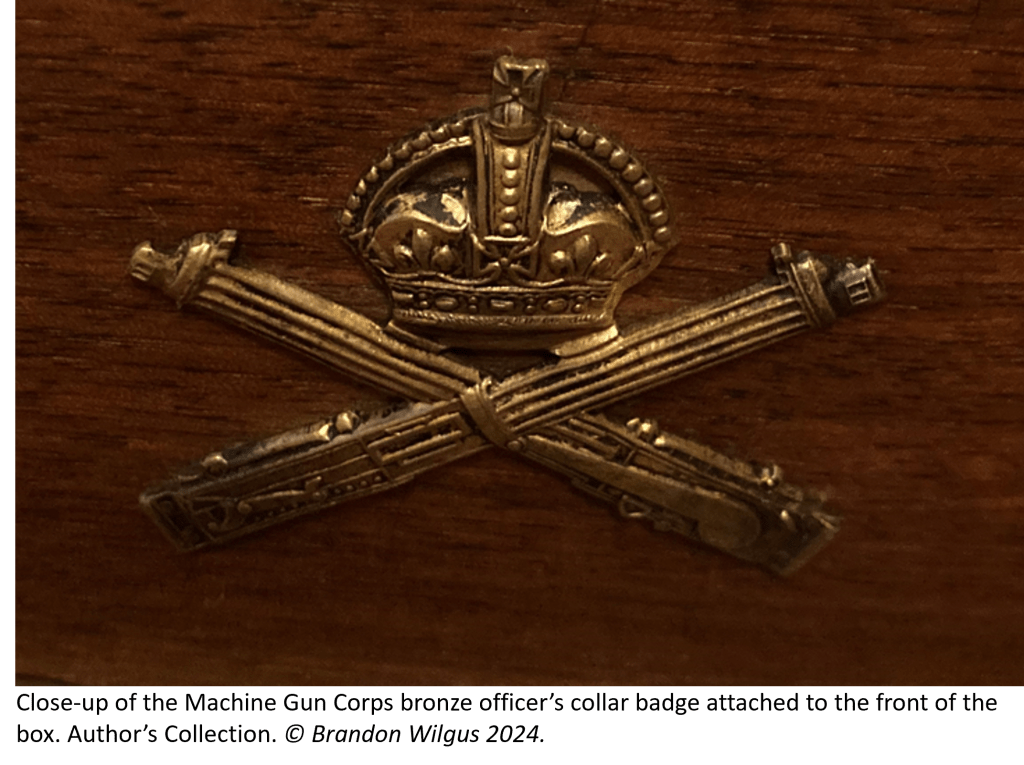

It was October or November 1917, a British soldier in the Machine Gun Corps took some scraps of wood, possibly duckboards or pieces of an ammunition container, and crafted them into a money box for his son back home in England. He found a way, and time, to cut the wood, screw the pieces together, sand and varnish the box, and then hammered an English and French coin to the top, flanking the slot he chiseled out. He then took an extra collar badge of the Machine Gun Corps, the organization of which he was undoubtedly proud to belong, and softly hammered it into the wood on the front of the box – the hammer taps are still visible in the bronze. Finally, after the varnish had finally set in the cold and wet of the Western Front – one imagines the box in a place of honour, drying by a stove in the muck and mire of a dugout – he turned the box around and hammered a note to his son with a nail point: “To ALFIE from DAD XMAS 1917”. He sent it off in the post, hopefully to arrive safely by Christmas for his son Alfie in England.

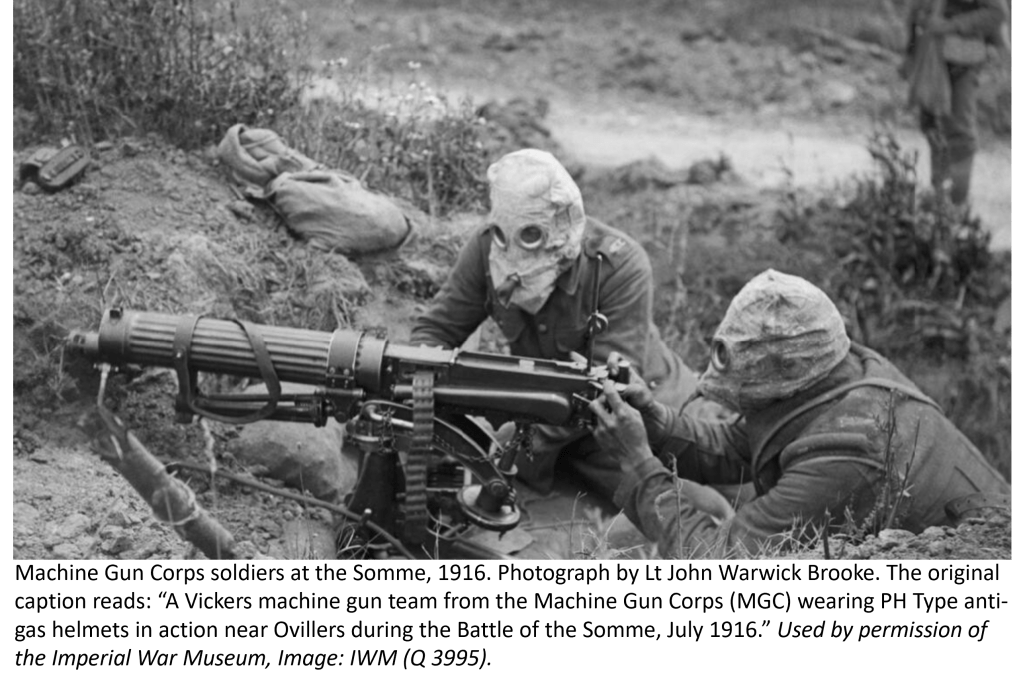

Alfie’s father was a member of the Machine Gun Corps. This prestigious force was formed in late 1915 with the aim to improve the effectiveness of the use of crew-operated machine guns in support of Allied infantry and cavalry units on all fronts. In 1914, each infantry battalion or cavalry regiment went to war with two machine guns embedded in the unit, this was quickly raised to four. By 1915, the Army realised that machine guns were being employed in a sub-optimal fashion, and a correction was in order. The Machine Gun Corps was formed in October 1915 by taking the Maxim and Vickers gun sections from all infantry regiments and consolidating the force to provide specialized training and specific marksmanship to crews to improve the use the machine guns on the front. By 1916, the Machine Gun Corps was divided into four branches: infantry, cavalry, motorized, and heavy. Most machine gunners were trained on the grounds of Belton House, a stately home just north of Cambridgeshire, near Grantham in Lincolnshire and would go on to support the infantry.

Life in the Machine Gun Corps was not easy – its members served on all fronts in the Great War – and the force was nicknamed “the suicide club” due to its heavy casualties. The enemy, observing the importance of the machine gun sections to both defensive and offensive operations, specifically targeted machine gun positions, mainly through artillery fires. By the war’s end, 170,500 officers and men served in the Machine Gun Corps, 62,049 became casualties, just over 36 percent of total strength. 12,498 members of the Machine Gun Corps died during the war. Seven members of the Machine Gun Corps were awarded the Victoria Cross, two posthumously. The machine gunner’s grit and bravery was unquestioned.

The Machine Gun Corps was short lived. It was disbanded in 1922 to save money after the war, but its legacy lives on in the Royal Tank Regiment. The heavy branch of the Machine Gun Corps was the first to operate tanks in combat on the Western Front, forming the Tank Corps when seperated from the Machine Gun Corps in July 1917. This force became the Royal Tank Corps in 1923 and now forms the Royal Tank Regiment.

This box, this gift from a father to his son at a time when at least one of the two realised they might not meet again, is the most precious and sentimental type of trench art. It was a gift to a family member made with what was available and at hand at the time. It leads to more questions than it answers: did the father make it home by the next Christmas, in 1918, after the war ended? Did Alfie, who received the box 107 Christmases ago, keep and cherish this gift from his father? Did Alfie ever learn of the experiences, the suffering, the pain that his father must have experienced while in France with the Machine Gun Corps? What became of the box after the Christmas of 1917?

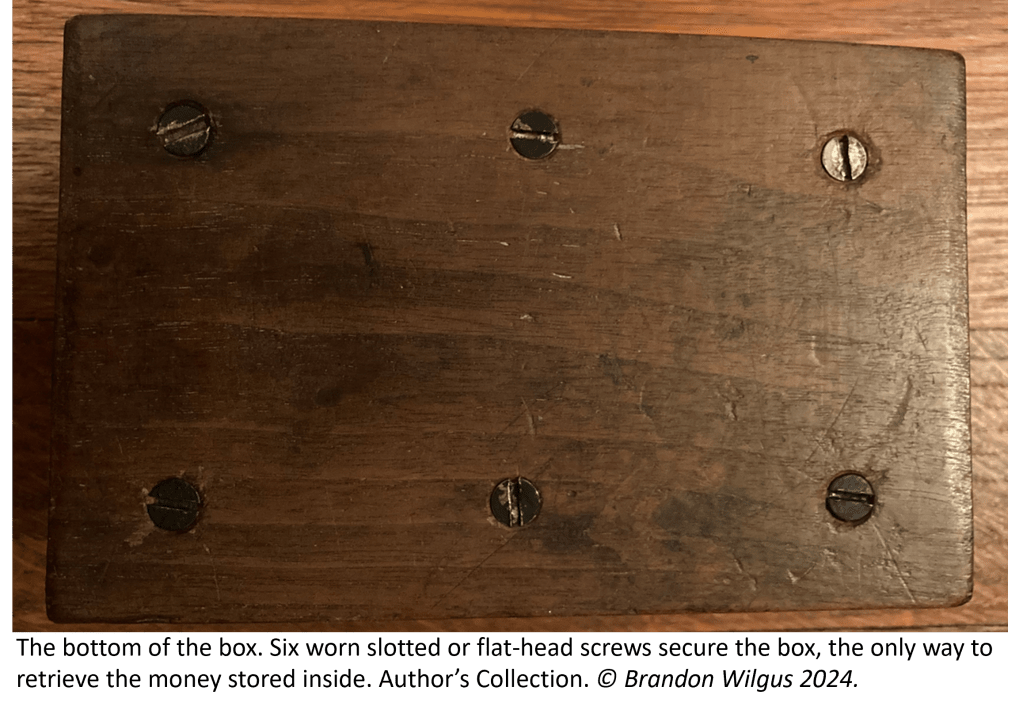

I can answer some of the last question. The box was obviously used to save coins for a long time, the slot on top is worn from the rough edges of many coins dropped through. The screws on the bottom – the old-fashioned slotted or flat head screws that one sees in Victorian or Edwardian furniture – have been taken out and screwed back many, many times. It was the only way for Alfie, or others, to retrieve the money they had saved.

What about the father? I assume he was commissioned, for the collar badge is an officer’s: it is bronze. Besides that, there is very little to learn of him.

The box eventually ended up in an antique store in Tewkesbury, a market town in Gloucestershire, and came to me for a few pounds. It now sits proudly on my shelf, as I am certain it once did on Alfie’s.

Recently, as my family was decorating for Christmas, I found myself hoping once more that Alfie’s father made it home from France a year after he made this box and was rejoined safely with his family. I hope that Alfie, and his father, shared many Christmases together in later years. Maybe a bit sentimentally, I wonder if 107 years ago, as this box was being assembled in the cold and misery of France in 1917, if its maker could have imagined it would be cared for and kept by a different family in England over a century later?

While a box like this will always spur more questions than it answers, I would like to tell you how I appreciate the questions and comments you send my way through the year, a very Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year to you all!