On 15 July 1099, Jerusalem fell to the armies of the First Crusade. Their stated goal, as the soldiers poured into the city set on murder, rape, and pillage was to wrest the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and other holy places from the Armies of Islam and establish a Christian Kingdom with its capital at Jerusalem. These Crusader States would stumble on but effectively ended in 1291 when the Kingdom of Jerusalem fell after the siege of Acre. The last stronghold of Outremer (the term used by the Frankish knights, simply French for overseas), Acre fell to the Mamluks and despite numerous additional Crusades, the Levant would remain in the control of a succession of Islamic States until seized by the British and French from the Ottoman Turks in the Great War.

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre was built in the early 4th Century during the reign of Constantine the Great. According to tradition, it contains both Golgotha, the site of Jesus’ crucifixion, and the tomb in which he was buried and rose from the dead. It underwent both Byzantine and Crusader modifications and changes, but its round design was established and known by the Middle Ages across Europe.

After the First Crusade, newly established religious orders such as the Knights Templar (Poor Fellow Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon) and the Knights Hospitaller (Order of the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem), along with pilgrims who had visited Jerusalem, returned to Europe and built churches which emulated the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Mimicking the circular shape seen in Jerusalem, a handful of Round Churches were built across England recalling the site in Jerusalem of Christ’s passion and resurrection.

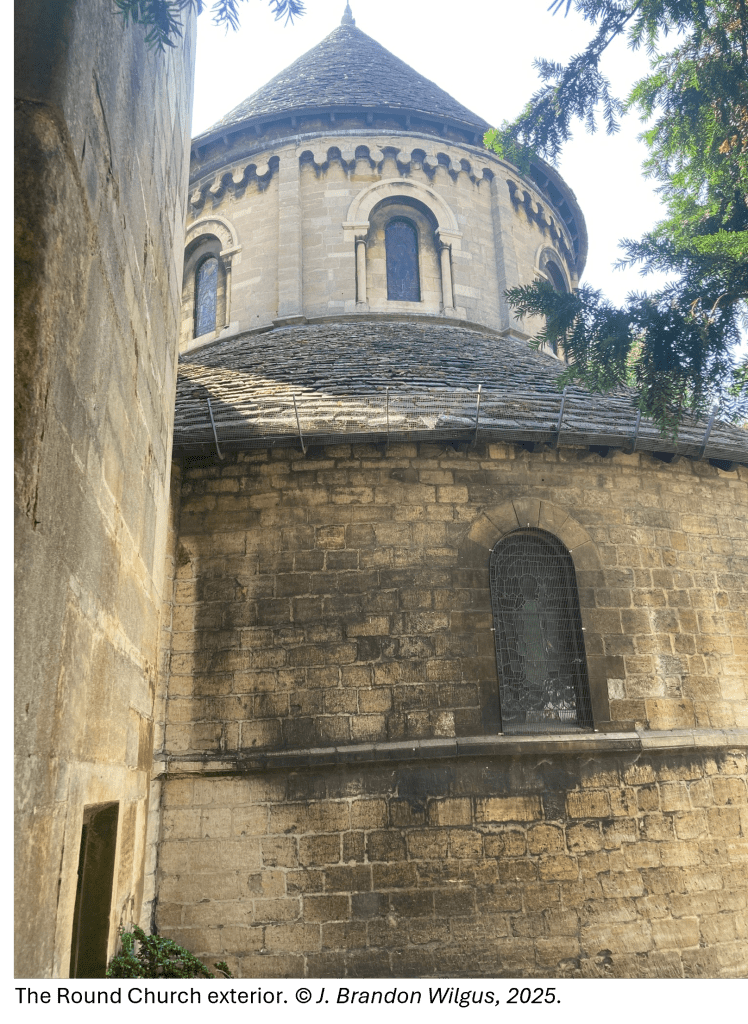

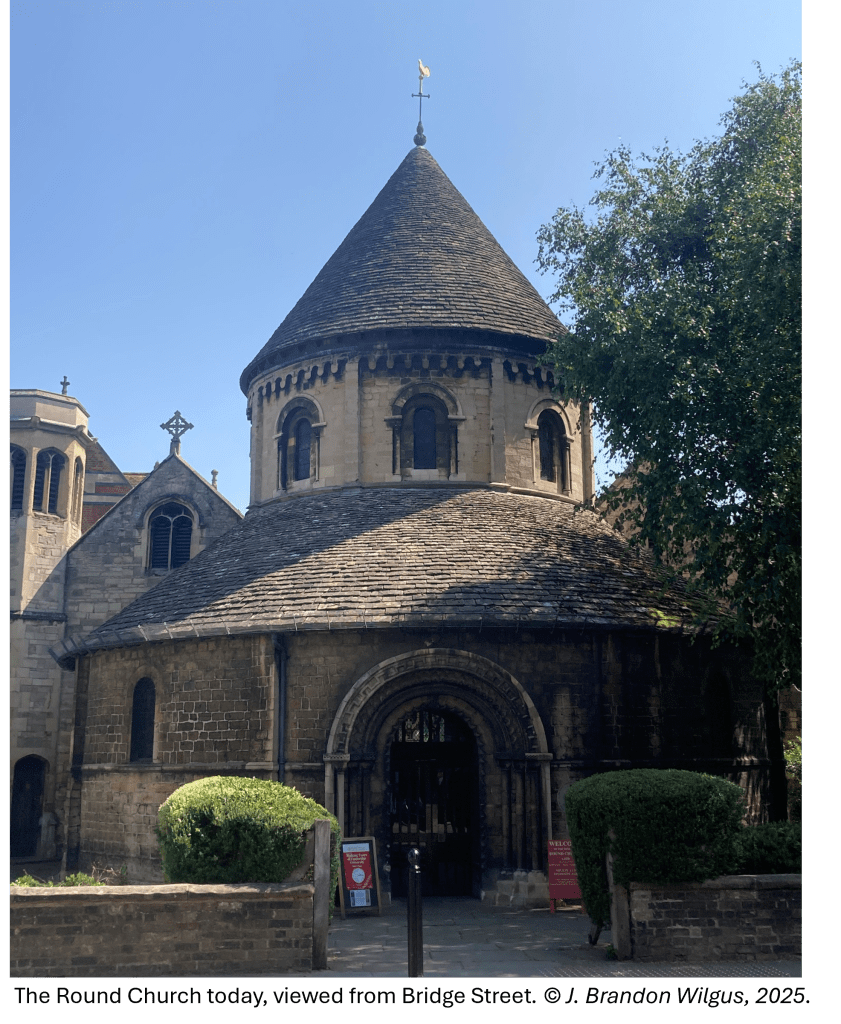

Between 1114 and 1131, only 15 years after the fall of Jerusalem, the Round Church in Cambridge was founded by an obscure group which we know little about which called itself The Fraternity of the Holy Sepulchre. In fact, there is no other record of this group except from this one project, and it was likely formed for the sole purpose of building the Round Church in Cambridge. The Fraternity claimed that the construction was “in honour of God and the Holy Sepulchre”. Consecrated as “The Church of the Holy Sepulchre”, it has been commonly called “St. Sepulchre’s” or simply, “The Round Church” since the 13th Century. This predates Cambridge University by almost a hundred years.

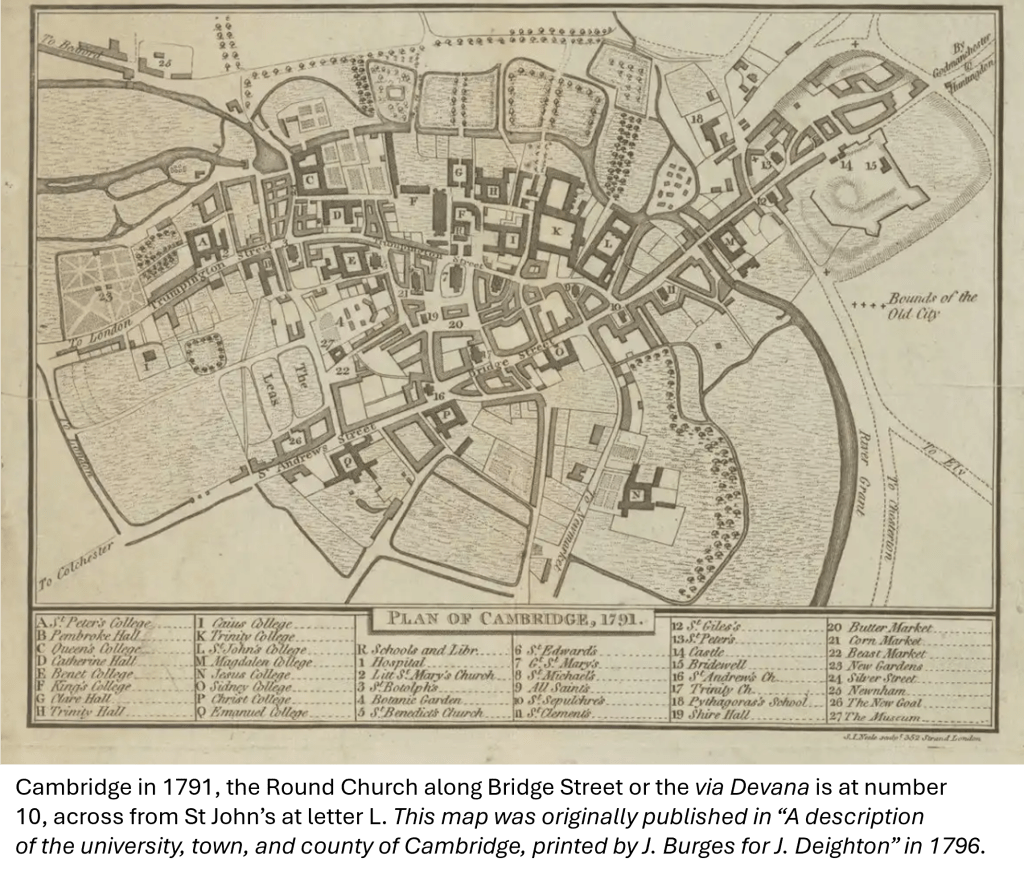

The first vicar of the Round Church was recorded as Geoffrey of Alderhethe in 1272. He was the Master of the Hospital of St. John the Evangelist, a religious hospital which resided across Bridge Street from the Round Church. (Bridge Street today is the old Roman Road, the via Devana, which ran from Huntingdon to Cambridge, crossed the Cam, and passed the Roman Fort of Duroliponte which is now Castle Hill.) The medieval Hospital is now St. John’s College, part of the University of Cambridge.

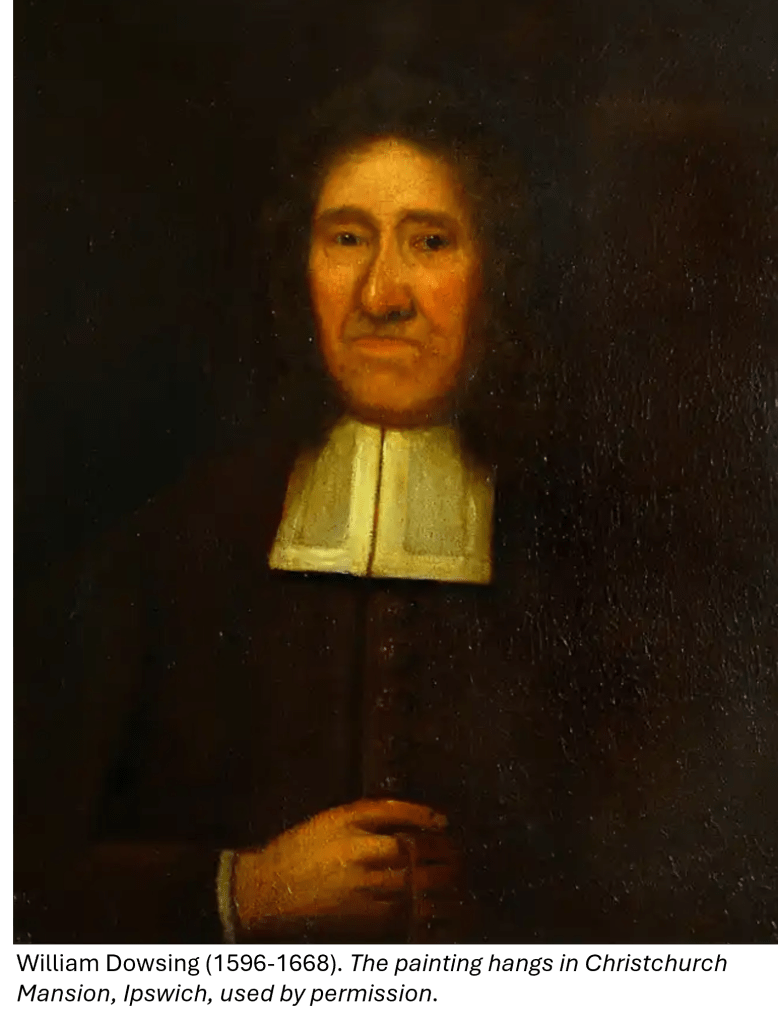

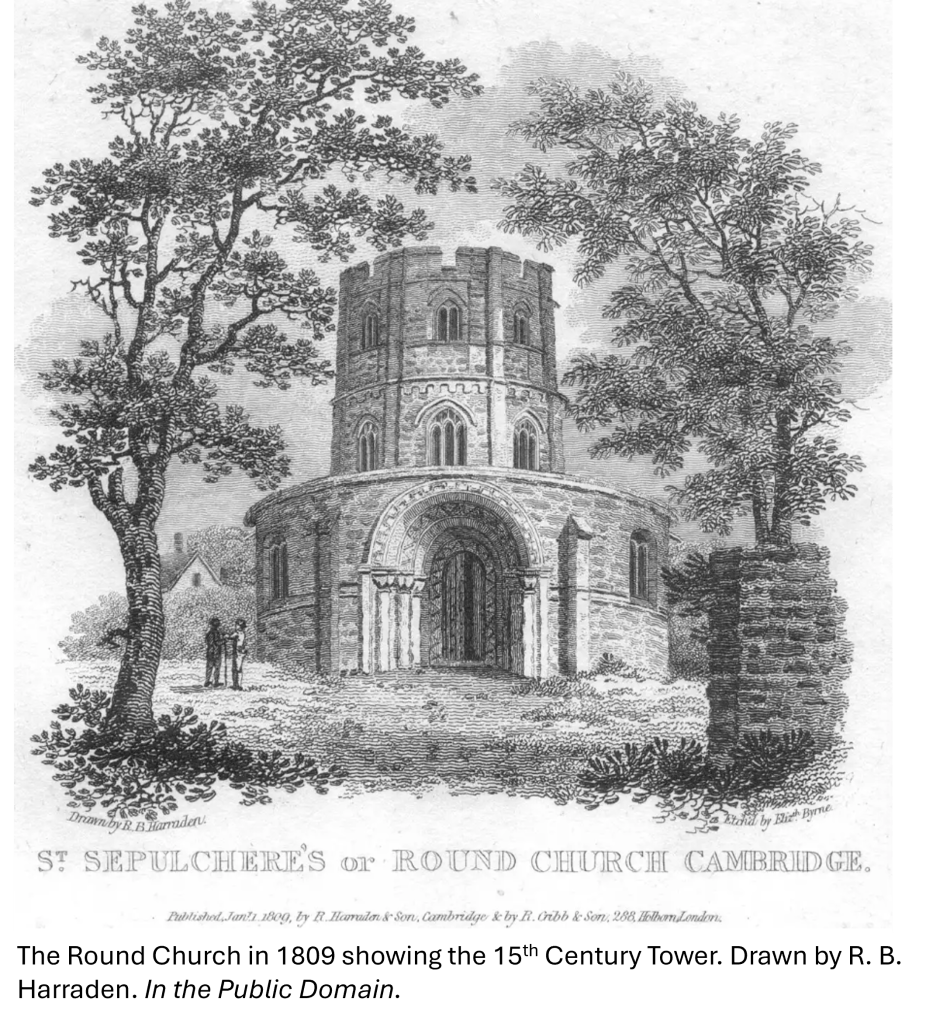

Expansions and extensions occurred over the next centuries, including a crenelated, multi-story tower which was added to the centre of the church in the 15th Century. At the same time, the Norman windows were replaced with larger, arched gothic windows. The church remained mostly undisturbed until 3 January 1644, when the Puritan officer and notorious iconoclast William Dowsing, known as “Smasher Dowsing”, arrived. Following the Parliamentary Ordinance of 28 August 1643 that “all monuments of Superstition and idolatry should be removed and abolished”, he and his soldiers destroyed fourteen pictures in the Round Church during the Civil War.

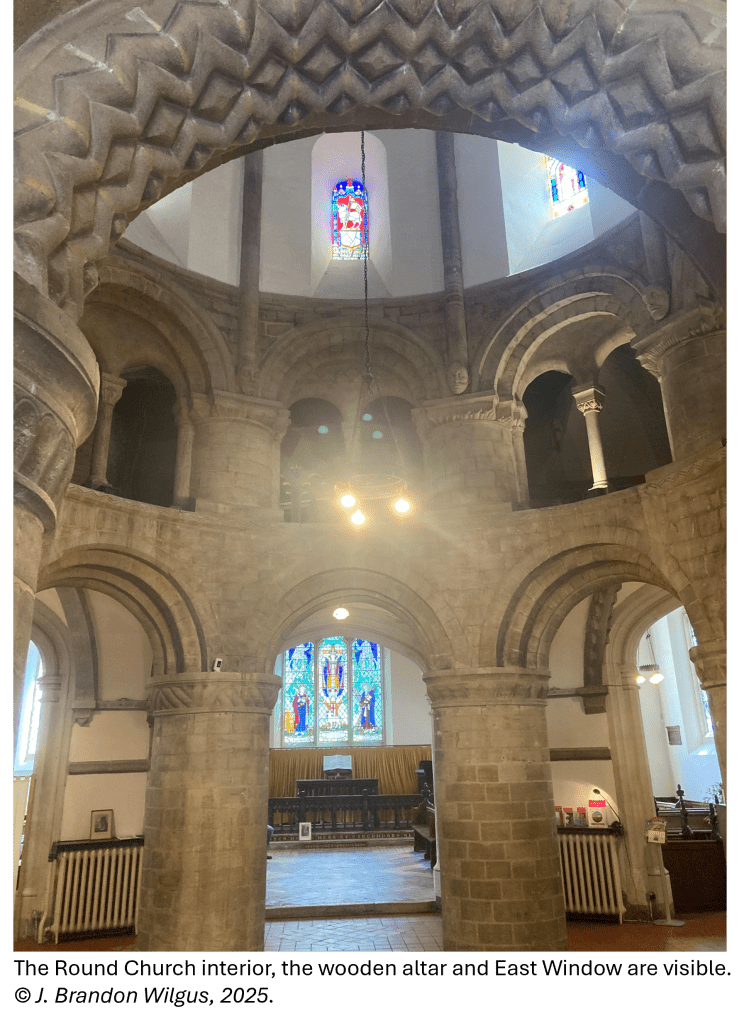

In August 1841, the 15th Century tower collapsed, damaging the original structure and threatening the entire church’s existence. A subscription for public support occurred and money raised for the church to be returned to its former glory. In October 1843, with Queen Victoria and Prince Albert in attendance, the church was reopened after its reconstruction, returning it much to its original form. The upper portions of the church were returned to their Romanesque origins, the Georgian box pews were removed, and the gothic windows were restored to their original design. However, the reconstruction was not without controversy. The Camden Society, which coordinated the reconstruction, had a stone Altar and Credence Table placed in the nave, which was seen as too High Church, popish and Catholic. A general outcry led to a well-publicized court case and in January 1845 the altar and table were ordered removed and replaced by more humble, wooden tables which can still be seen today.

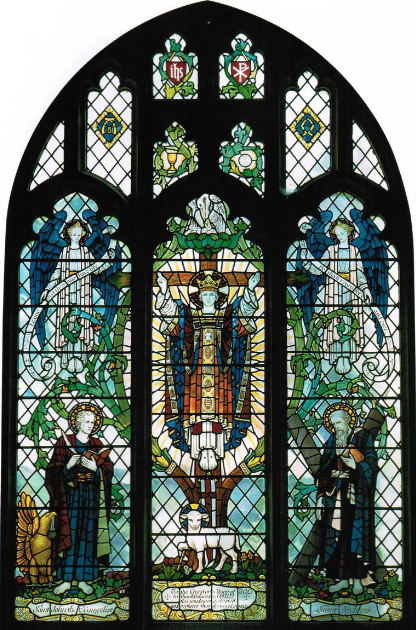

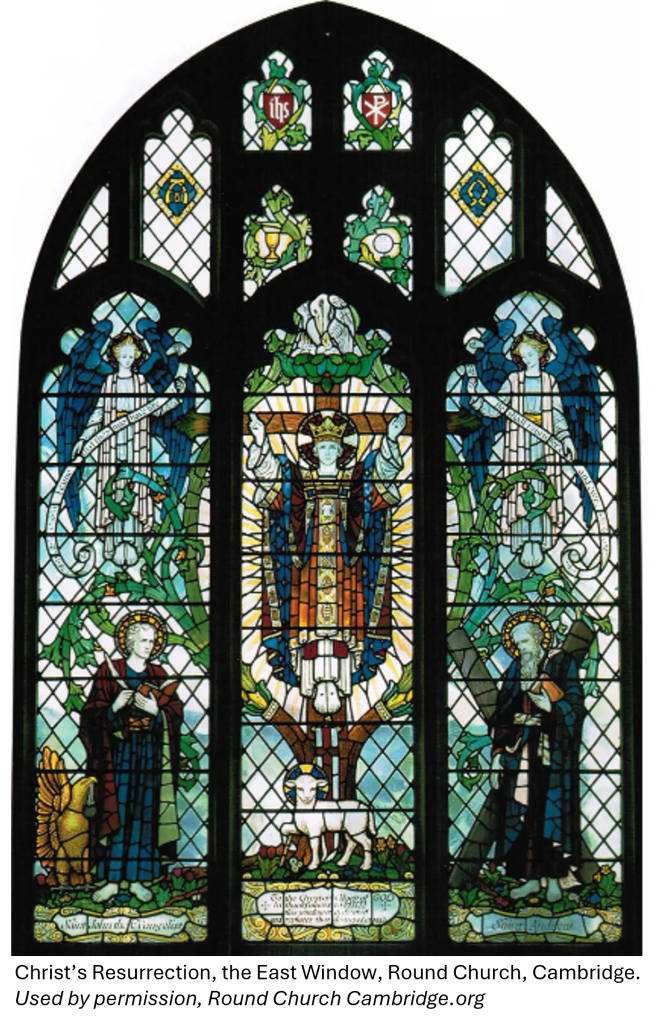

One would have thought there would be no more war damage to the Round Church after the iconoclasm of 1644, but on 28 July 1942 a single German bomber dropped its ordnance of high explosives and incendiaries on Cambridge. The bombs did extensive damage along Bridge and Sidney Streets, killing three people and wounding seven. One bomb struck the Cambridge Union Society Building, which had been built on the Church’s former graveyard, causing the medieval stained glass in the East Window to be blown out and destroyed. After the war, the window was beautifully replaced with new stained glass showing Christ’s Resurrection, which occurred on the site of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem.

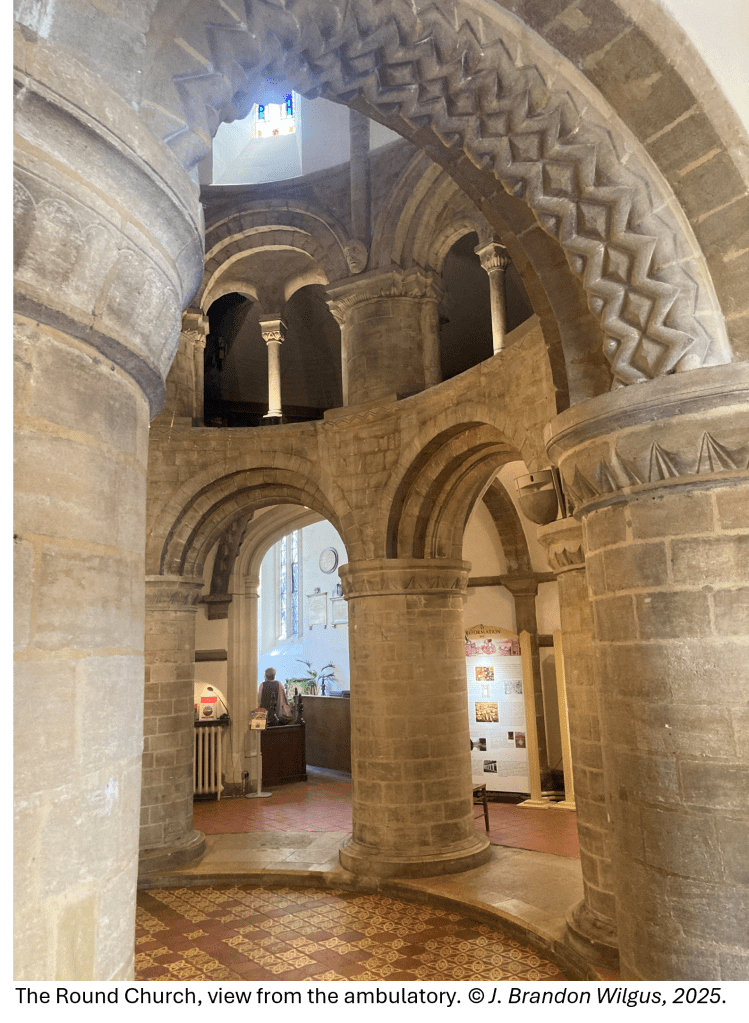

Inside, the church strikes a visitor as both beautiful and small, focused more on the center of the Round Church than the altar which rests in the nave, surrounded by the raised ambulatory. Eight thick Norman columns with round arches break the ambulatory and the nave and hold up an upper floor. Much of the stained glass is from the Victorian era restoration and from the 1946 window which repaired the German war damage. The tiled floor, which includes Queen Victoria’s coat of arms, dates from the 1841 restoration.

The Round Church Cambridge is one of four remaining medieval round churches in England. The others are the Temple Church in London, The Holy Sepulchre Church in Northhampton, and the Church of St. John the Baptist in Little Maplestead – all beautiful with a fascinating history and worth a visit.

To find out more about the Round Church’s visiting times, walking tours, and events see https://roundchurchcambridge.org/

To learn about its architecture and its evolution over the years, visit: https://drawingmatter.org/the-future-of-the-past/

To learn more about the church’s restoration, see Chris Miele’s “The Restoration of the Round Church, Cambridge”, English Heritage, Historical Analysis & Research Team Reports and Papers (First Series, 5), 1996.

To learn more about the bombing raids on Cambridge during World War II, visit Cambridge Historian: https://cambridgehistorian.blogspot.com/2012/07/world-war-2-air-attacks-on-cambridge.html