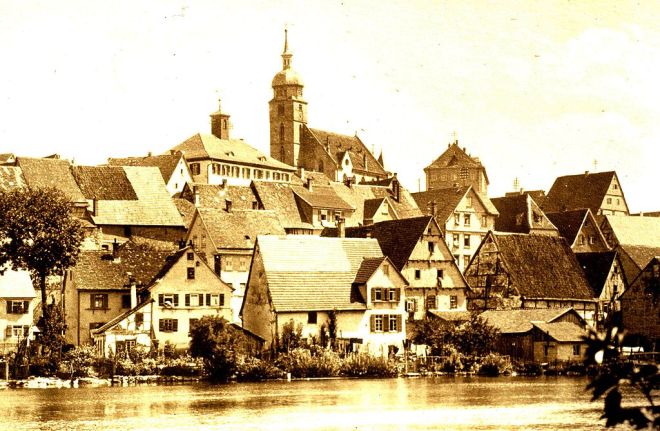

Located between Huntingdon, Godmanchester, and Brampton Village is a low-lying meadow along the River Great Ouse. Having existed as a protected place since medieval times and known as the largest meadow in England, Portholme Meadow is treasure. The site was historically dubbed Cromwell’s Acres due to his connection with the area and the nearby presence of Hinchingbrooke House but it is Portholme Meadow’s early connections with aviation in Cambridgeshire that I want to explore. While the meadow is a wildlife paradise, a Site of Special Scientific Interest, and an important part of managing flooding in the area during the winter, it is its aviation history that is an almost forgotten story and a key piece of Cambridge military history. At 104 hectares, wholly located in the Brampton Parish, the Portholme Meadow was used as a Royal Flying Corps and RAF training area during the later part of the Great War and beyond, but its connection with aviation began earlier.

In 1910, just two years after Samuel F. Cody had flown the first aeroplane in England, James Radley, an early aviation pioneer based in Bedford believed that the flat areas of the Portholme Meadow, shielded from winds, and accessible to local towns, were ideal for take-off and landing as well as demonstrating to an enthused public the wonder of flight. Having acquired a Beleriot monoplane (the French aviator had recently flown the channel and the Alps), on 19 April 1910, with almost the whole population of Huntingdon, Godmanchester, and Brampton watching, Radley took off and flew circuits of the meadow to the amazement of the local crowds.

While several flights were made, Radley’s aircraft was able to complete a 16.5 mile circuit of the meadow at an altitude of 40 feet in just under 24 minutes – just over 41 miles per hour.

After this success, a workshop was aquired in Huntingdon, on St. Johns street, and James began to assemble his aircraft along with his partner Will Morehouse. Their company, Portholme Aerodrome Ltd. was founded and the first locally produced aeroplane was flown on 27 July 1911 from the meadow.

Despite local enthusiasm, Radley and Moorehouse’s business venture was not a succes. Their debts mounted and they were unable to produce a commercially viable aircraft. In 1912, they sold Portholme Aerodrome Ltd. to Handly Page which also struggled to maintain profitable aircraft production in Huntingdon. However, flying did continue in Portholme Meadow up until the Great War, largely for practice and demonstrations for the public. When the Great War began, the admiralty awarded Handly Page a license to produce 20 Wight Seaplanes for the Royal Navy, but this contract was canceled in 1916 after only four aeroplanes were produced due to issues with the construction. Consummed with debt and the war over, Portholme Aerodrome Ltd. went into receivership in July 1922.

However, it was later in the Great War that the Royal Flying Corps, which became the RAF in April 1918, used the meadow for flight training, and this use would continue into the 1930s. At one point, the Portholme Meadow was considered for conversion into an airfield, but luckily this never occurred, and this beautiful and unique piece of nature was conserved. As aircraft became larger and maintenance requirements grew, the RAF moved the remaining aircraft from the grassy meadow to RAF Digby in Lincolnshire and Portholme Meadow’s brief history with aviation came to an end.

If you would like to visit Portholme Meadow, it can be accessed from Godmanchester, Huntingdon, or Brampton but I would recommend parking at The Brampton Mill, Bromholme Lane, Huntingdon, Cambs. PE28 4NE, where the Meadow can be accessed by public footpath – and an excellent lunch or pint can be had after your visit.

Sources:

Doody, J.P., Portholme Meadow: A Celebration of Huntingdonshire’s Grassland. The Huntingdonshire Fauna and Flora Society, 60th Anniversary Report, eds., H.R. Arnold, B.P. Dickerson, K.L. Drew and P.E.G. Walker. 2008.

Hull, Patrick. 1998 – The Past of Portholme. The Godmanchester Museum Website: http://www.godmanchester.co.uk/bridge-magazine/219-1998-the-past-of-portholme