I have been fascinated by Trench Art for several years. I was first exposed to numerous examples of decorated shells, paperweights, desktop items, and trinkets made in the areas around Mons and Ypres, Belgium where we lived some time ago. Some of these items I acquired and began a small collection. First though, what is Trench Art? At its most basic level, it is handcrafted artwork made by soldiers and sailors who find themselves with free time and materials to create original works of art. This was often men stuck in the trenches of the First World War, or in Prisoner of War (POW) camps from the Napoleonic Wars through World War II. Items were made as souvenirs to post home or carry back on leave, to trade, or to simply occupy time in a dangerous and horrifying situation. One feels that a soldier felt very little control over his circumstances and fate, surrounded by destruction, but could find a release through an act of creation. There are numerous items one can find: decorated brass shell casings are common, but also letter openers, desk items, regimental items, matchbook holders, ash trays, models of ships, aeroplanes, ships, and so on. The beauty of Trench Art is in its originality, its story, the story of its materials, who might have made it, and why?

According to Nicholas Saunders, who has written on the history and variety of Trench Art, there are four real categories of the craft: items made by soldiers in war; items made by POWs; items made by civilians at the front with access to materials; and finally, purely commercial items. The first three categories are the most interesting to me; however, around Belgium one often finds examples of the fourth category. Often one finds decorated shells made to sell to families traveling to Flanders in the 1920s – the Menin Gate or some other poignant memorial often is depicted on these items.

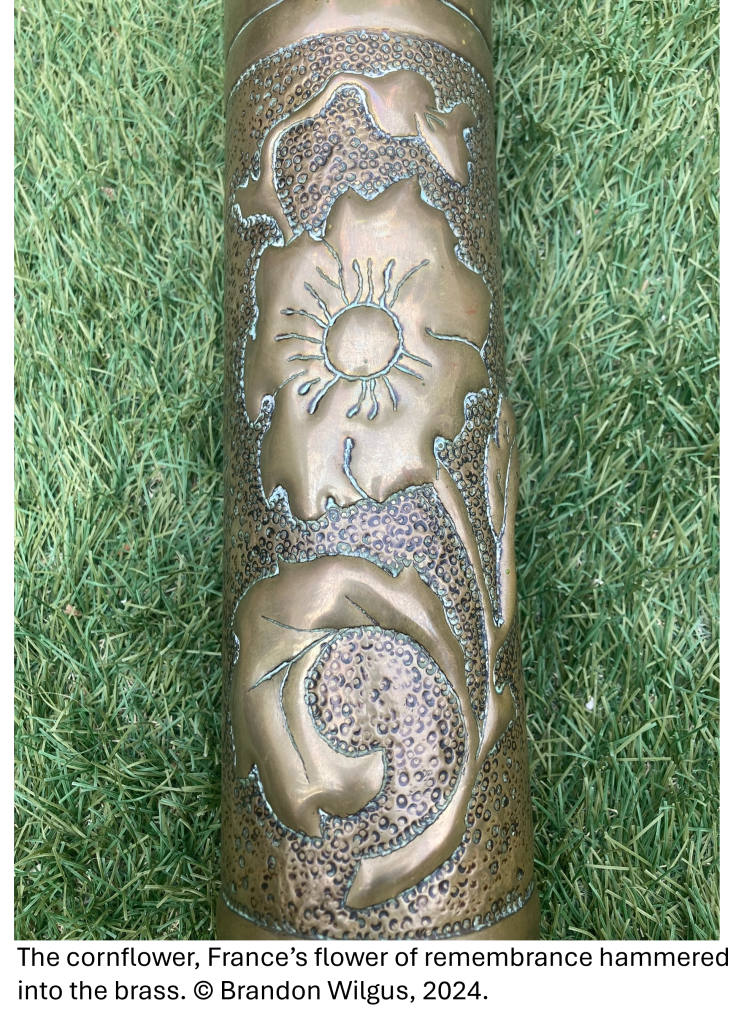

We are currently traveling in southern France on holiday. While exploring a local marché aux puces, a flea market, I found a decorated French 75-millimetre brass shell, with 1917 hammered into the lower part of the vase below a stylized cornflower. The cornflower in light blue is the symbol for remembrance in France, like the red poppy in the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth Nations, or the gold star or yellow ribbon in the United States. The base of the shell reads: “75 DE C, C. 793 L. 17 C”. As time has gone by, these markings have become harder to decipher, but the “75 DE C” means 75 canon de compagne, or the 75mm quick-firing field gun, which is the gun for which the shell was made. The “C. 793 L.” is the munitions manufacturer and the lot number, so C is for Castelsarrasin, Tarn-et-Garrone, which was the location of a major armaments factory in southwest France under the Compagnie Française des Métaux (CFM) concern. This shell in particular was part of that facilities’ 793rd lot of 1917. The “17” is the year of manufacture, 1917. The final “C” is the initial for the foundry which made the brass for the shell, also CFM’s Castelsarrasin factory in this case.

I find it interesting to delve into the history of these decorated items, these mementos made during such awful times. What makes this piece of Trench Art fascinating is that after this shell was manufactured and fired in 1917, a French soldier likely took the time to hammer a cornflower and the year into the brass, then blued the indentations. He almost certainly made this piece of art in 1917 soon after the shell was fired since the brass casings of fired rounds were collected, recycled and reforged by French armaments manufacturers desperate for raw materials late in the war. The shell vase was then kept for 107 years until it came into my possession at a French flea market this week. There are many questions which are unanswerable: where on the Front was this 75mm shell fired? At whom or what? Who made this specific piece of Trench Art? Did he survive the war? Was it a gift for a wife, a sweetheart, or family member? Maybe he made it to trade or to sell? Who kept it, cherished it, and preserved it for over a century? One question I can answer, the cost in 2024? 107 years after it was made on the Western Front, lovingly preserved, and eventually forgotten, it made it into a box of old bits of metal and cost me 8 Euros on a hot Saturday in southwest France.

For more information on Trench Art, I’d recommend an excellent book on the subject: Nicholas J. Saunders, Trench Art: A Brief History and Guide, 1914-1939. 2nd Ed., (Barnsley: Pen and Sword Books, 2011).